When Andrea Knabel’s friend Heather went missing outside Lexington, Kentucky, on September 1, 2017, no one knew exactly what to think. Some of Heather’s friends and family back home in Louisville (about 80 miles away) suspected a kidnapping, that perhaps her boyfriend, who they say was a drug dealer, may have been holding her against her will. Others knew that Heather, who was last seen leaving a Salvation Army shelter, was battling a mental health episode, was homeless, and could veer toward self-harm. Moreover, she had an active arrest warrant against her, and, her friends said, openly struggled with alcoholism.

Knowing the trouble Heather often found herself in, frequently announced via her own Facebook posts, some of those who knew her wrote her disappearance off as just another erratic episode. “She had some really crazy paranoia going on,” a friend who was close to Heather in college, tells me. “I knew there were drugs [involved].” With Heather missing, “to be 100 percent honest? I just shut it down” and stopped thinking about it, the friend says.

Andrea Knabel did not. One of Heather’s best friends since childhood, she reported Heather missing to the Lexington Police Department. A mother of two boys, and the oldest of three sisters, Andrea had long been known among friends and family as someone who tended to overlook a person’s demons in light of their angels. (Growing up, her sisters called her “Mother Andrea” for her unconditional caretaking, a name that stuck in adulthood.) Andrea spoke with a soft Appalachian drawl, sometimes laughing with a voluminous snort, and in pictures she often had parted ash-blonde hair and a smile that appears unmistakably genuine. “Andrea was just really, really high energy,” Suzzette Rodriguez, Andrea’s friend for the past decade, says. “You could be in the worst mood ever, but when she walked in the room your mood just changed.”

Soon after filing the police report, Andrea heard from Nancy Schaefer, the founder of Missing in America, a group of volunteer missing persons sleuths, who offered to help with Heather’s case. Andrea accepted Nancy’s offer and, near the end of that September, they got together and made it their mission to find Heather and either rescue her or, if she had skipped town willingly, convince her to return home.

“We fear that she is a victim of human trafficking,” Heather’s friends wrote on Missing in America’s page, “and that there is only a small window of time that we have to help save her life.”

Andrea was afraid that someone might have taken Heather against her will. She and the other volunteers convened in Lexington to pursue a tip that Heather had been spotted wandering alone underneath a viaduct in the Loudon neighborhood on the east side of town. Because Andrea’s sister Sarah Knabel and her boyfriend, Ethan Bates, knew Lexington well (they were living there at the time), Andrea directed them to comb the Loudon area. They eventually came across Heather, who promised them that she and her boyfriend would meet them all back at Sarah Knabel’s house in Louisville.

Heather did not show up. Four days passed. Suzzette and Andrea kept looking and ended up spotting Heather’s boyfriend at a Speedway gas station. The two women confronted him and — according to a Facebook post Andrea later wrote — somehow managed to get ahold of one of his diamond earrings. They told the boyfriend that he wouldn’t get his earring back until Heather came home. It worked: She finally showed up later that day.

It was during this search for Heather that Andrea befriended Nancy Schaefer. Nancy is a former accountant from New Jersey, who says that she put her entire savings into Missing in America’s grassroots method of search and rescue—think Guardian Angels meets overactive Facebook group—to take, as Nancy likes to put it, “the cases that are unpleasurable for others.” Nancy had already helped investigate the murder of 29-year-old Tromain Mackall, she says, and she assisted local activist LaCreis Kidd in the search for her daughter, Nayla, the case that first brought her to Louisville. During her time there, Nancy brought on several new volunteers, but she was most wowed by Andrea.

Photo of Andrea Knabel with her sons on Mother’s Day; her sister Erin posted this image to Facebook in 2021. (Photo courtesy of Erin Knabel)

“She was like a chameleon,” Nancy says, explaining that Andrea could switch from being “very professional” to talking “street lingo.” “She was able to turn herself into these two roles.”

“From here on I can just hope that my friend chooses to make better choices,” Andrea wrote on Facebook. “And I want her to know that she has so many friends and family that love her and are here for her.” In a photo accompanying the post, Heather stands embraced by Andrea, Sarah Knabel and another friend. It’s still unclear exactly what happened to Heather during the time she was missing. “Andrea finding her made her feel like she really had a friend,” says Diane Stumph, a former member of Missing in America. “That somebody cared for her.” (“Heather” did not respond to requests for comment but expressed to friends that she does not want any publicity. So, given the sensitive nature of this case, Narratively opted not to publish her real name.)

Nancy, who would develop a tight relationship with Andrea over the next two years, says that the particular thrill of the search for Heather awakened a new purpose in her newest volunteer. But Andrea’s investigations would eventually come to run parallel with her own unfortunate downfall.

Nearly two years after Heather’s disappearance, in the early hours of August 13, 2019, Andrea herself went missing.

Tracy Leonard likes to tell new recruits that he was more or less forced into the career of a private investigator. After eight years of working as a small arms and artillery expert for the U.S. military, his knees and face were maimed in a tank accident. In 1994, in his late 30s, he was honorably discharged as a disabled veteran. Back home in Clarksville, Indiana, Tracy figured that law enforcement was his best career path stateside, and he applied to the police academy that year. Due to his reliance on a cane, however, he realized securing a badge would be unlikely. Instead, he took up apprentice work with a veteran detective, who told Tracy he had two possible paths: Join the Army Reserves as a part-time soldier, or work as a private investigator. “At that point, I chose to be a P.I.,” Tracy, a father of four with a short stature and a square jawline, says. “Hell, I wanted to make some money.”

Tracy has spent more than two decades developing his reputation as a go-to investigator in the Northern Kentucky region. By 2015, he estimates he had helped find “about 40 to 50” missing persons, mostly young Kentucky women, successes that he says earned him the nickname “The Locator.” That year he changed his company’s name to Loc8tors — better branding, he says — and expanded the company to 17 full-time investigators, including his twin brother, Ted, a former painter and celebrity bodyguard who, like Tracy, speaks in a mix of Appalachian twang and Midwestern affectation.

Everyone at Loc8tors has their own call signs: “Dick Tracy” for Tracy; “Robocop” for Ted. The Loc8tors hail from a wide avenue of law enforcement and security detail: from retired Louisville Metro cops to parole officers and bail bondsmen. Due to a staggering caseload of workers’ compensation stings and infidelity scandals, Tracy is known to train newcomers via exhaustive trials by fire, rather than by-the-book regiments. “It kicked my ass at first,” says Jacob Nix, the Leonards’ brother-in-law and Loc8tors tech specialist, describing his training with the agency. “But here, you kinda just get thrown into the shit.”

The Leonard brothers first came to work with Andrea Knabel when they were investigating the case of a 17-year-old who went missing outside of her parents’ home in Fern Creek, a suburb of Louisville. Nancy Schaefer had sparked a connection with the Leonards during her first months in Louisville. She gauged Tracy’s interest in a possible documentary about her missing persons investigations, and boasted about the great work Andrea had done during the search for Heather. Tracy talked to Andrea and decided that her interrogation skills were a good fit for the case. “Andrea seemed more professional, more articulate” than other Missing in America members, Tracy tells me. “It seemed like she’d done this all before.”

While still working her day job as an analyst for the health insurance company Humana, Andrea began volunteering with the Loc8tors. She traveled to the missing girl’s high school in nearby Fern Creek to question teachers about the young man the girl was apparently smitten with.

“She convinced the teachers to let her search the girl’s locker,” Tracy recalls. “And found the kid’s first and last name and birthdate in one of her notebooks.”

After a background search, Tracy found the boy’s address and drove to his home in Kansas City. The family gave him little information, so he interviewed their neighbors, who told Tracy that some unused license plates had been stolen from their garage. He ran the plates. Days later, Tracy drove up to a one-story gray home in Kansas City, across the street from a Walmart. He spotted a cat in the front window of the house. The missing girl’s mother confirmed via text message that it was her daughter’s Chartreux cat. Kansas City police officers raided the home. Detectives told Tracy Leonard that the girl was found chained to a radiator in the basement, and likely would have been trafficked, possibly to Mexico, where the boy was from.

For most of the following year, Andrea grew into her new shoes as a volunteer searcher. In August 2018, she and Nancy led a Missing in America caravan up to Chillicothe, Ohio, where the team combed through dense woods for signs of a missing 22-year-old woman who had just fled a rehabilitation facility in Columbus after a crack cocaine relapse. (Her body was ultimately located by Chillicothe police in the basement of a fellow rehab member. She had overdosed.)

Leveraging Diane Stumph’s four decades of doing investigative work as a producer and camera operator, Nancy hired her to bring along a film crew, determined to present the footage to Randy Tat, a producer in Los Angeles she had connected with. “It was just an extension of us helping people at the time,” says Suzzette Rodriguez. “I thought, with the reality show, it would give us more exposure, more names out there.”

Randy Tat recalls being impressed with Andrea. “She’d do the research, would make the PowerPoints,” he tells me. “She was great at being organized.”

Andrea and Nancy also searched for Bret Broffman, Jr., a 27-year-old music festival diehard whose abandoned car was found outside Glasgow, Kentucky, after Broffman drove to Bonnaroo music festival in June of 2017. The Missing in America team sifted through dense underbrush and back roads for signs of him. After Broffman’s clothing and a femur bone were recovered by detectives, Nancy says Andrea “fought viciously” on behalf of Missing in America to have Broffman’s alleged suicide — he had died of a gunshot wound — reclassified as a homicide. On May 8, 2019, after Broffman’s remains were confirmed, police announced a criminal investigation.

By 2018, Nancy says she had developed a tight emotional bond with Andrea, more so, it seems, than she did with other Missing in America volunteers. One time, when Nancy went into anaphylactic shock during the search for Broffman, Andrea was the one who waited at her bedside in the emergency room. “That was just who she was,” Nancy tells me, “always there for you.” In September 2018, needing a place to stay, Nancy moved into an apartment on Louisville’s south side with Andrea, Andrea’s children, and one of Andrea’s childhood friends. Nancy also asked Andrea to be the maid of honor at her wedding.

It was around this time that Nancy says she began to grow irritated with certain other members of Missing in America. Instead of abiding by proper search and recovery etiquette, the others, she says, were going against protocol, and she feared that they were prone to contaminating crime scenes. Perhaps the pressure to legitimize Missing in America in documentary form was putting extra stress on a team that already operated as a bare-bones volunteer effort. “They were showing up [to searches] in flip-flops and sundresses,” Nancy says, in a tone wavering between gripe and sorrow. “Dealing with law enforcement is a whole different ball game.”

Suzzette Rodriguez and Diane Stumph dispute this, asserting that they maintained professionalism throughout 2018’s Missing in America caseload. “It’s not rocket science,” Suzzette says. “You don’t touch anything without a glove, you take down coordinates. When it’s your group, and her members aren’t doing things right, that’s on her.”

“I’ve been doing this for 40-plus years, for god’s sake,” Diane adds. “I know what I’m doing.”

But cracks in Missing in America’s loose band were soothed, Nancy says, by what Andrea could offer: a particular ability to do this kind of work. Andrea “always put 150 percent into it. She had skills no one had,” Nancy adds. “Unfortunately, good people make bad decisions.”

The small suburb of Audubon Park is known as one of the Louisville area’s safest places to live. Located southeast of downtown, Audubon Park has its own police force, golf course, country club and bird sanctuary. It’s known for its dogwood trees; the streets are wide and breezy, populated by authoritative signs that read “No soliciting” and “No parking.” “People will call the authorities … over anything,” says Erin Knabel, one of Andrea’s younger sisters. Growing up here, “it would be normal for someone to call the police [and say], ‘Hey! Your friend walked in my grass!’ You know?”

The Knabel sisters grew up in Audubon Park, on Chickadee Road, which dead ends into St. Stephen Martyr, the Catholic school where the sisters all went to elementary. To their father, Mike Knabel, it was evident early in Andrea’s life that she had academic gifts that matched her social butterfly personality. “She was making A’s without even trying,” he recalls, sitting in a chair in his spacious living room near the Ohio River. “I remember the tests. She was in the top two or four percentile in some of those areas.” Andrea’s mother, Cheryl, and Mike — the two divorced when Andrea was 13 (and Cheryl did not respond to interview requests for this article) — sent Andrea to a nearby magnet middle school to challenge her, and then to Assumption High School, where, Mike boasts, “95 to 97 percent of the people go to college.” Her grades there, he says, showed true talent. “There was no limit to where she could’ve gone. Where that could’ve taken her.”

Andrea later graduated from the University of Louisville with a degree in marketing. She worked a series of odd jobs for three years, including as a CVS district manager and a server at the Tumbleweed Tex-Mex restaurant. After ending an eight-year relationship, she had two sons with two different men. She never married.

Around 2009, in order to support her family, Andrea got a job as a group Medicare analyst at Humana. Co-workers say that she excelled at her work, at first, and she was unflinchingly active in team building, whether it be lunchtime gym workouts, group kickball or after-work cocktails at Applebee’s. Loyalty to those she trusted, co-worker Whitney Nechelle says, was paramount. “She’d be the friend I’d take to a bar fight,” Whitney says. “She’s a spitfire.”

In 2017, Andrea brought a 34-year-old car detailer named Brian Downey home to Christmas dinner at Mike’s house. Mike says that Brian, with his shaved head, myriad tattoos and off-color jokes, seemed like a complex character. Though Brian presented himself as a reformed father of three — he’d gone to school to be a respiratory therapist — he had also been arrested multiple times, for offenses ranging from car theft to, on one occasion earlier that year, wandering around a Walmart naked and high on methamphetamines, after burglarizing a woman’s home. (According to Erin Knabel, the episode earned Brian the nickname “Naked Walmart Man.”)

Regardless of Brian’s colorful record, he sold a better version of himself to the Knabels. “It appeared that he had settled down, and maybe learned his lesson, and maybe was going on the right track,” Erin says. But, “later on, as they dated, months after that, I realized that wasn’t the case.” (Brian Downey did not respond to a request for an interview as this story was being reported, then he passed away suddenly in January 2022, shortly before this article was published.)

In the eyes of Andrea’s friends and family, Brian’s entry into her life precipitated a downward spiral reminiscent of the very people she’d been working to find at Missing in America. She began living with Brian in March 2018, which further concerned her friends and family members. Believing that Brian was involved in Louisville’s drug underworld, co-worker Tarica Dow says she questioned the tough integrity of the Andrea Knabel she thought she knew. “Her decisions with men sucked,” Tarica says. “Insecurity will make you settle for anyone that gives you attention.”

For months, Mike and Erin watched as Andrea and Brian’s relationship bounced from let’s-make-do sweethearts to both sides making wrathful, jealous threats. In spring of 2018, he proposed. At Humana, her co-workers had their palms over their mouths. Whitney Nechelle recalls her surprise when Andrea posted a picture of the ring: “What the hell? Girl, what are you thinking?”

The wedding never came to fruition. On July 6, 2018, Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD) officers pulled Brian over. They found enough meth (more than 2 grams) in his car to warrant a drug trafficking charge. Brian was sent to prison. To Andrea’s family, this was good news. Andrea, it seemed, would get a chance at redemption. “When he got arrested, I thought, ‘Good! Maybe this’ll be the end of her problems,’” Erin says. “She’ll start over and get back on track.”

Those hopes did not pan out. Despite Brian being out of the picture, Andrea’s friends say she still fell into questionable relationships on account of her “Big Heart Syndrome.” By September, when Nancy and Andrea were living together, the relationship between the two closest Missing in America members gradually began to fray. Nancy recalls their shared “slumlord”-run apartment falling into disarray, and while she didn’t know it at the time, she now believes Andrea started using meth in lieu of her prescription Adderall. “Andrea was running with the wrong crowds,” Nancy says. “There were strippers [hanging] out on the couch, drug dealers coming up in and out of the home. ‘This is my home! I help pay the bills!’” In December 2018, credit card debt led Andrea to file for bankruptcy for a second time. Concurrently, she was dealing with a child custody case involving one of her sons. And, by winter of that year, she’d lost her analyst job during a companywide layoff — although a work friend, Tarica Dow, says that Andrea was fired due to poor performance reviews and not waking up until noon.

Although Mike kept silent through most of the chaos that befell his daughter, that year was a breaking point for him. He often spent late nights on the phone with Andrea, helping arrange rides for her after her Nissan Maxima broke down on the highway and was totaled by a snowplow, or sending her money to soften her 2018 bankruptcy. He wanted Andrea to admit herself, as he says, to “a hospital for help.”

By spring of 2019, Andrea was living on food stamps, and soon she could not afford the apartment where she and Nancy had been living. Effectively homeless, Andrea moved into her mother’s home — the house on Chickadee where the Knabel sisters had grown up — while Andrea’s sons’ fathers handled the majority of caring for the boys. That summer, Mike exploded. “I read her the riot act,” he says. “I said, ‘You lost your job. You’re homeless. You don’t have a car. You don’t have any money. You’re in debt. You can’t afford your children.’”

However, he also offered her “help and hope,” he says. “I wanted her to hit a bottom where she would bounce back.”

Nancy, for her part, moved to her sister’s place in Pennsylvania in July 2019, to take an emotional breather. She divorced her husband (they had already been separated for some time) and took time to reflect on the Louisville days from afar.

Others, like Suzzette and Diane, had already begun to sour on Nancy and her efforts at self-promotion, and now they questioned her overall credibility. They point to an unfortunate episode in July of 2017, in which Nancy filmed a YouTube video with a woman named Michelle Hooper. Nancy claimed that the woman was actually Jennifer Klein, who had gone missing from a campground near Moab, Utah, in 1974, when she was 3 years old. As missing persons breakthroughs go, this one was as big as it gets.

But Nancy was wrong. Michelle’s DNA was analyzed and the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System determined it wasn’t Jennifer Klein’s.

“It’s no secret that Missing in America had a rough go,” Nancy tells me. But she points to the apparent misbehavior of her former colleagues. “I mean, when you’re a person that wants to make a difference, and members don’t want to follow protocol? I take it personally.” (“Nancy, I think her heart’s in the right place,” Erin Knabel tells me, “but she doesn’t get along with anyone that long.”)

Back at the house on Chickadee, Andrea was living in a bizarre kind of reunion. A month earlier, her other sister, Sarah, and Sarah’s fiancé, Ethan Bates, the dark-haired owner of a Lexington construction company, had also begun staying at Cheryl’s home — rent-free, Mike makes sure to note. Cheryl’s pipes had burst in her upstairs bathroom, so she’d hired Ethan, and by extension Sarah, to do what was initially expected to be a quick job. But a month and a half later, on August 12, 2019, not even the grout was done. Mike laughs at the ridiculousness: “Apparently they were having a good old time over there,” Mike says, “and not doing a whole lot of remodeling.”

The nine and a half hours between 9 p.m. on August 12 and 6:31 a.m. on August 13 have been dissected by so many — Reddit users, YouTube psychics, multiple reporters at the Louisville Courier-Journal, six private investigators, two police detectives, and thousands of members in half a dozen Facebook groups — and their different interpretations of the night’s events often completely contradict one another. After analyzing a dozen accounts from Andrea’s family and friends, along with reviewing relevant Facebook posts and text messages, as well as LMPD’s official timeline of events, here’s what we know about what happened to Andrea Knabel that night.

Around 8 o’clock, after eating takeout Chinese food from the nearby Double Dragon, Andrea got into an argument with her mother, Cheryl — “Nothing out of the ordinary” for their family, Erin tells me — and this folded over into a scuffle with Sarah and Ethan, whose criticism, Erin suggests, had veered toward becoming violent. (Sarah and Ethan did not respond to requests for interviews.) At 9:50 p.m., Andrea, suffering from either an eczema breakout (common among the Knabel women) or stress-induced face picking, was dropped off at a hospital a few miles away, after having been driven there by Ethan, who was also accompanied by Erin’s teenage son. Afterward, Andrea took a Lyft back to the house on Chickadee, arriving at 11:34 p.m. Irritated, Ethan and Sarah did not let Andrea in.

At 12:15 in the morning, teary-eyed and overheated by the balmy August heat, Andrea walked one mile south to Erin’s fixer-upper on Fincastle Road, a dense low-income neighborhood full of multifamily townhomes. Erin was drinking a glass of wine with her neighbor Michelle when Andrea arrived, and she could immediately see the distress on her sister’s face. On the front porch, Andrea told Erin about the fight, how Sarah was echoing Cheryl’s attack, and how Andrea was failing her own sons. To calm her, Erin invited Andrea inside the apartment and let her watch television while Erin’s two younger kids tried to sleep in the living room. Erin phoned Cheryl — who was not at the house on Chickadee at the time, but rather at her sister’s place — urging Cheryl to tell Sarah and Ethan to let Andrea back in.

At 1:03 a.m., Erin dropped Andrea off at her mother’s home. No more than seven minutes later, she received a text message from Andrea: “They won’t let me in the house.” At 1:15, Andrea reentered Erin’s apartment from the unlocked back door and once again implored her hesitant sister to let her stay the night. “Please,” Andrea begged Erin, “I’ll sleep on the floor!” Erin refused; Andrea, volatile and on edge, was too much of a liability. (“If you stay with me, you will ruin our lives,” Erin texted Andrea the next day, suggesting that she’d had to apologize to her neighbors so that they wouldn’t try to get her evicted.)

In her tank top, shorts and Nikes, Andrea walked down Erin’s stoop, took a left on the Fincastle sidewalk, passed about three dozen homes, crossed the tiny bridge that links Fincastle Road and Audubon Park, and has not been seen by anyone since.

The two-plus years since Andrea disappeared have produced an endless grab bag of ideas about what happened, captivating armchair detectives and social media onlookers everywhere. Some of the theories, none of which have been confirmed by LMPD, stretch the imagination: Distressed with the animosity from her family, Andrea walked away from her life and fled to an unknown location in Indiana or Ohio; Andrea returned to Cheryl’s home on Chickadee, phoned a “friend” for a ride, and that “friend” killed her; Andrea was coerced into a vehicle after leaving Erin’s and kidnapped; Andrea walked off and then committed suicide (every family member and friend I interviewed wholeheartedly rejects this theory); or, in what may be the most bizarre theory proposed by the myriad internet sleuths, Andrea and her friend Nancy are in secret cahoots, leveraging her unique case — the searcher who becomes the searched for — for Missing in America’s benefit.

“I have no motive! I was in Pennsylvania [at the time],” Nancy says in response to this idea, adding, “Andrea was a very valued friend of mine.”

In 2020 alone, 59,369 women over the age of 21 went missing in the United States, yet only a small sliver of them — usually white women — get national media attention. Andrea’s case has been featured everywhere, from a four-part Finding Andrea miniseries on Investigation Discovery (produced by Randy Tat, the filmmaker Nancy had connected with before Andrea went missing) to a recent segment on Dr. Phil. It also has its own subreddit. And, just as the Missing in America cases did for Andrea, now her own case has become fodder for fellow female searchers.

“This will have to be one of the most taboo cases I will probably have to cover,” said Zahara Hasina Willis, an actress who discusses true crime on her YouTube channel Mystery Muze and believes Andrea could have skipped town. “She was actually volunteering to find missing people — and now she’s missing. This is insane.”

Melissa Ellen, who brings awareness to missing persons cases on her YouTube channel True Crime History, has wrestled with the hoax theory, noting: “people feel, still to this day, that [the Jennifer Klein incident] was all part of Missing in America’s ploy to pull a hoax off, to get their views up, and get some clout,” Ellen said in a 30-minute video. “That is a possibility, and that’s what a lot of people are putting out there.”

The disparate theories have often pitted searchers against one another, including those who were closest to Andrea. Nancy has created a Justice for Andrea Knabel Facebook group, which, instead of adopting Missing in America’s heartfelt cadence, communicates in a mostly accusatory tone, asserting that the Knabel family, Erin included, are not disclosing everything. (“Why does Erin still leave posts up that are blatant lies?” one post reads. “What is her motivation? Does this type of dishonesty help efforts to find Andrea or hurt them?”) The result is a ceaseless volley of accusations: Each side believes that the other is either withholding knowledge or refusing to cooperate with the cops about the accurate timeline of events.

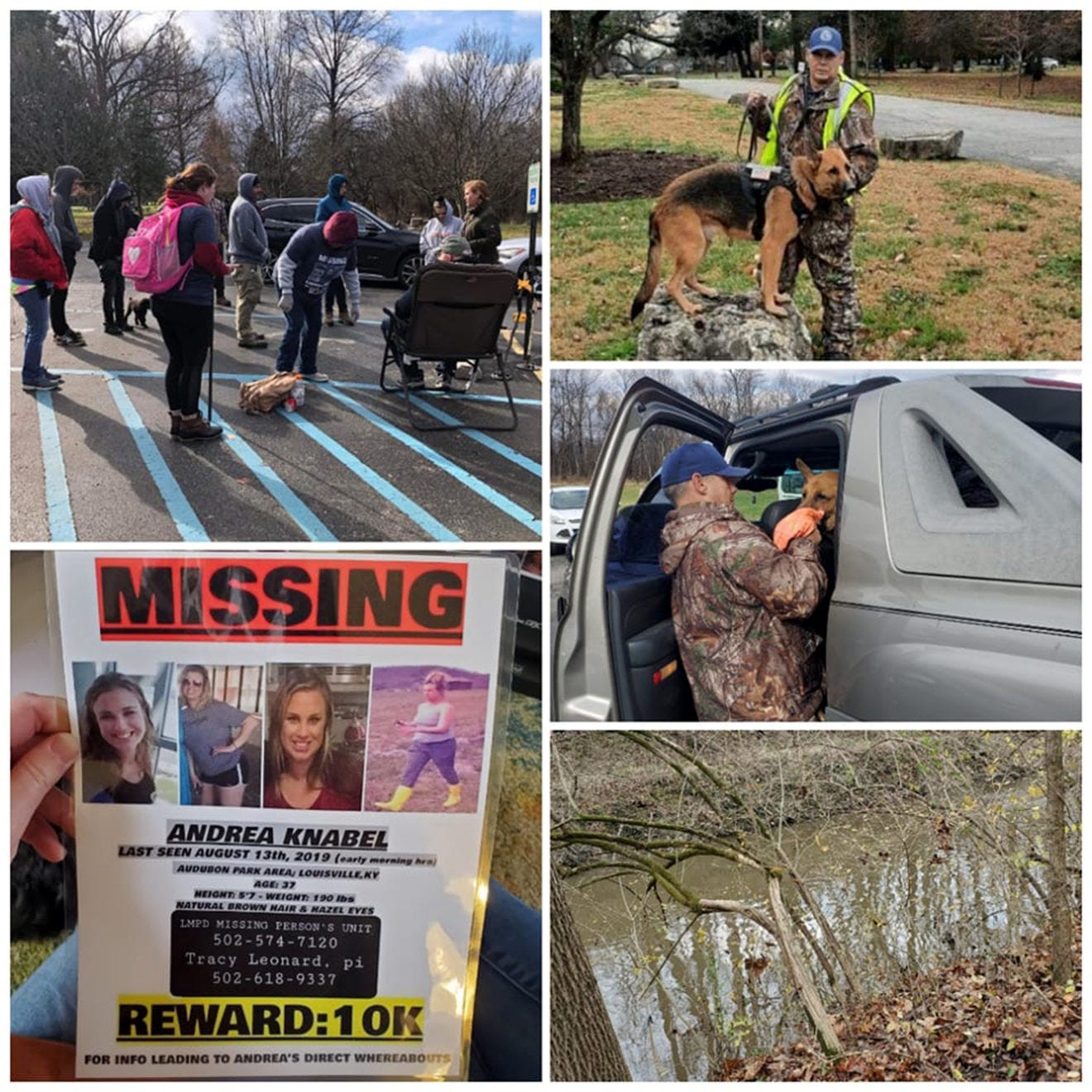

This division has led to a sour taste in the mouths of past Missing in America members. At first, in August of 2019, Nancy, Suzzette and Diane performed their own searches, knocking on doors along Fincastle Road in hopes of getting witness testimony or camera footage. Vigils were attended. Flyers were posted. Searches were orchestrated near the Ohio River. Michelle Freeman, a mother of three who joined Missing in America at the start of Andrea’s case, says that at first the search for Andrea was honest and heartfelt. Then, a month into the case, emotional tensions between the members began to derail any focused effort, which Michelle chalks up to what she calls Nancy’s “abusive” behavior and profanity-laden management style. “There were times I just came home and started crying,” Michelle says in a phone interview. “You’re doing everything you can to find Andrea Knabel — and nothing’s good enough.”

Two months after Andrea went missing, Suzzette, Diane and Michelle left Missing in America, they say, due to frayed ties with its founder. In their minds, the search for Missing in America’s lost member was legitimate and necessary, yet nearly “impossible,” Michelle says, with Nancy at the helm.

“It was never about Andrea,” Michelle says. “It was about fame, money, attention, what can I get out of it.”

Nancy, for her part, disagrees: “I’m a good person who’s made sacrifices for this cause. But I need to protect myself,” she tells me in a text message, adding: “This was about Andrea.” She has declined to comment any further. As far as her organization, she says, “Missing in America is no longer. I’ve walked away from everything.”

As for the police, although LMPD did perform the requisite dog searches in 2019, their enthusiasm softened, Tracy Leonard says, “as soon as meth came into the picture.” (LMPD rejected a request for an interview for this article, but it did provide its own timeline of events, which is similar to the one provided by the Leonards, with only a few small discrepancies.)

The only thread these rival parties agree on is that Ethan Bates is an undeniable person of interest. Several of these investigators say that they suspect him, for a multitude of reasons: Ethan and fiancée Sarah have refused all interview requests — including one from Narratively — except for a two-hour interrogation that LMPD did shortly after Andrea disappeared. Ethan pled guilty to cocaine possession in 2009, and the Leonards suggest that he, like Brian Downey, is linked to the vast Kentucky meth market. In the summer of 2021, LMPD said in a statement that its detectives attempted to perform a polygraph test on some members of Andrea’s family and were denied.

Some, like Victoria Quibbel, who know Ethan believe that he was the ultimate source of the conflict on August 12, 2019, that apparently led to Andrea’s disappearance. “I 100 percent think Ethan knows what happened,” Victoria tells me. “And I’m almost certain that Sarah does too.” (Tracy Leonard also attempted to interview Ethan, who declined due to what he called “slanderous accusations” against him from Mike and Erin.)

As for Sarah’s possible involvement in her older sister’s disappearance or murder, Mike can’t find the energy to even entertain the thought. Like his daughter Erin, he’s spent the past two years mired in a routine of posting flyers, checking out possible sightings, and talking ad nauseam to news reporters about Andrea and her work with Missing in America. For Sarah, and by extension Ethan, to be involved, Mike says, would be atrocious. “She hasn’t spoken to me in a year and a half,” he says. “She thinks I’m accusing them of everything. Which is exactly the opposite. Erin’s heard me say it’s my worst nightmare every time — that they would be responsible for anything to do with this.”

Ethan Bates remains just one figure among many whom the Leonard brothers have investigated over the past two years. Like the Missing in America team, they have endured a plethora of leads that have gone nowhere: walks around soup kitchens and homeless camps in response to reported sightings, long stakeouts at shady drug houses, thousands of calls from so-called witnesses, and wild attempts to swindle the $10,000 reward the Leonards have offered. (In one incident, a Louisville pimp in a Walmart parking lot tried to convince Tracy Leonard and Mike that one of the blonde sex workers whom he employed was Andrea.) In early 2020, the Leonards had assigned an investigator, Mark Baker, solely to Andrea’s case, and he spent up to 80 hours a week responding to witness calls or working surveillance. Tragically, Mark Baker died abruptly from a brain aneurysm in December 2021.

Tracy Leonard says he has been working the case pro bono, and he estimates that he and Loc8tors have spent more than $100,000 tracking down leads in four states. Both he and his brother Ted say that their persistence is necessitated by the state of law enforcement: LMPD lost 20 percent of its officers in 2020, many to transfers and early retirement, after Breonna Taylor was killed by LMPD officers and large protests broke out. Nearby police departments in Clarksville and Jeffersonville have helped the Leonards — accompanying them on a trip to a homeless camp, for example — yet LMPD, Ted Leonard says, “asked us not to interfere with their investigation.”

Nearly two years after the case began, the Leonards understood that if Andrea were to be found, it would likely have to be without much police collaboration. During a recent ride-along in his Chevy Avalanche, flanked by AR-15 rifles and a K9 dog named Duke, Ted Leonard tells me that police don’t want to share information with him: “Which is kinda crazy. We’re out here doing all the legwork, we’re out here knocking on doors, watching surveillance.”

In August 2021, Ted and Tracy were driving back from an unrelated surveillance job in Texas when they got a call. It was a Northern Kentucky area code, so Tracy picked up. The caller, whom we’ll call “Megan” here to protect her privacy, said that she was there the night Andrea went missing. Although he has fielded hundreds of calls like this, Ted says that the tone of Megan’s voice “made the hair stand up” on his arms.

“This lady was in-depth with detail,” he recalls. “You could hear it in her voice. She didn’t want the reward. Most people are calling for the reward: ‘Hey! Send me the money first and I’ll tell you where [she’s] at!’”

“I was there,” Megan is heard saying in the recording, which the Leonards shared with me. Her voice is fragile and sprinkled with sniffles, as if she’d been crying for hours before calling.

“Can you give me some details?” Tracy asks.

“She didn’t know what was going on,” Megan says. She says that Andrea was raped by several men, and killed, in a house that’s a 15-minute drive from Audubon Park. She gives the Leonards explicit details about how and where. Megan escaped, she says; Andrea did not. She tells Tracy that it was all at the hands of an African-American motorcycle gang.

“Do you know what they did with her body?” Tracy asks, matter-of-factly.

“I tried to stop it. I tried to stop it. I couldn’t.”

“I’ll tell you what. Can you give me your name, and it will stay confidential?”

“I can’t talk to cops.”

“I know … you won’t talk to cops, you’ll talk to me …”

“Was there any other girls there? Any other people present?”

“Yes, there was other girls.”

“And were they being held against their will?”

“Yes.”

“So is this a human trafficking issue?”

Megan sniffles after a short pause. “Yes,” she says.

Joe Fanciulli flew into the Louisville airport for the first time in January of 2021. A retired homicide detective at the police department in Lakewood, Colorado, he joined the growing ranks of investigators in Andrea’s case mostly out of pure interest. Unlike the Leonards, Joe prefers to work alone, and he seems to take voluminous pride in his skeptic’s view of the criminal world. “I care about one thing and one thing only,” he says. “Facts.” In December 2019, Nancy reached out to Joe for his thoughts on Andrea’s case. In January, the two started dating, and shortly after that, she moved in with Joe in his home outside of Venice, Florida.

Joe claims that he tried to meet with Tracy Leonard on multiple occasions, but that Tracy stood him up every time. Instead, Joe stuck to his trusty brand of orthodox policing — what he calls “Investigation 101” — bringing takeout pizza to question homeless people, knocking on neighbors’ doors on Fincastle and Chickadee, and surveilling known drug houses in Louisville’s rougher neighborhoods. A 74-year-old bike enthusiast who tends to sport aviators in photos, Joe conducted his research with caution: “There were always three of us around,” he wrote in one Facebook post: “Me, Smith & Wesson.”

Joe dismisses the outlaw motorcycle gang theory (as does the LMPD; the Leonards passed the mystery caller’s tip on to the police, but they say the police dismissed her as an unreliable source). He’s continually frustrated by the zigzagging nature of Andrea’s case. It’s “like the whack-a-mole game,” he says. “One scenario to the side, another pops up.” His rule of thumb, as with most missing persons cases, is to look at those closest to the victim first. He says he’s focused on Ethan Bates. He points to Facebook screenshots that show Ethan and Sarah “changed their minds” about their reactions days after the investigation opened. At one point, Ethan said that he and Sarah wouldn’t let Andrea inside Cheryl’s house; but at another point he said they “were asleep.”

Last spring, Joe walked the same path Andrea is believed to have taken the night of August 13, 2019. He wanted to replicate her exact footsteps, looking for unseen clues, so he started at the steps of Erin’s house on Fincastle, and eventually, after 20 minutes, crossed the short bridge into Audubon Park. Standing near Cheryl’s home in the wee hours of the morning, Joe says he felt like he was at square one yet again. How, he thought, could a 37-year-old, tough-as-nails mother go missing here? “There were people on bicycles, people with dogs — no Black bikers,” he says, verging on laughter and disbelief. Being there pushed Joe to narrow down the possibilities. “Either something happened to her at that house,” he concludes, “or she reached somebody who came and got her, and that somebody might have been somebody she shouldn’t have called.”

The premiere of Finding Andrea has brought even more attention to the case, and the docuseries, which relies heavily on testimony from Nancy and Joe, only seems to have exacerbated the disputes between Nancy and some of the former Missing in America members. Randy Tat, the producer who first met the Missing in America crew back in 2018, says that he’s aware of the former members’ feelings about Nancy. But, he says, “I don’t know that side of her. I know that she’s a big personality, type A. Underneath it all, I think she’s had the best intentions.” He says that his team strove to “make a candid, authentic” documentary and that the discord among the various participants is disheartening. “It bothers me that there’s so much destruction and animosity, and watching it play out on social media just breaks my heart.”

In October 2021, after Finding Andrea debuted and exacerbated tensions between various players in Andrea’s world, Nancy, Joe, Erin and Mike all flew out to Los Angeles to appear on Dr. Phil, to discuss the case’s emotionally taxing nature and the resulting feud.

“You said, ‘In 50 years, this is probably the most complicated case you’ve worked on,’” Dr. Phil recounts to Joe. Nancy sits next to him, wiping her eyes. Joe discusses the “holes” in Tracy’s timeline, the whereabouts of Andrea’s phone, how “there are family members who have not been cooperative since day one.” As Erin and Mike wait patiently in a backstage green room, Joe suggests that Andrea’s sores were meth-related, not from skin picking, and that she was involved — undoubtedly — in the meth trade.

“I’ve been doing this for over 45 years, and I’m telling you nothing helps more than all hands on deck,” Dr. Phil tells Erin after she and Mike replace Joe and Nancy on stage. “You want everything. Everybody needs to be leading in the same direction here.”

“I agree completely,” Erin says.

“I think we should both work with them,” Mike adds. “And I think there is maybe a couple of trivial things that may have gotten loose on social media, and they should be all put behind us.”

Dr. Phil breaks eye contact, calling backstage to Joe and Nancy. “Can I broker a peace here, guys?” he asks. “I know the best for Andrea will come to pass much faster if all four of y’all are working together.”

The camera switches back to the green room. Joe agrees, citing a commitment to Mike that seems to transcend the theatrics of television. “The last thing I said to him was, ‘I’m not going to go away,’” Joe says. “I’m not going to walk away from this.”

Two years to the day that Andrea went missing, on August 13, 2021, Erin and Mike Knabel retraced her steps from that fateful night. Just like Andrea, they went on foot , with Erin’s poodle, Luna, scrambling around on a leash, starting on Chickadee Street at 1:30 in the morning. Twenty minutes and 40 seconds of the walk was aired via Facebook Live, and later shared in the “Where is Andrea Knabel?” group, where Erin still posts updates almost every day. “I feel like if I don’t say anything,” Erin says in the video, “then people will just forget she’s missing.”

Throughout the entire video, both Mike and Erin say little to nothing, as if their minds are busy memorizing potential clues. Erin’s camera tilts to the water runoff under the Fincastle bridge. There are just a few people out, and as usual, Fincastle is dense with parked cars, a chorus of humming crickets and the yellow light of halogen street lamps. Two and a half minutes in, a viewer comments on the livestream: “Someone would have heard her screaming if she was abducted, it is so quiet.” Erin responds, “My thoughts exactly.”

In September 2021, three weeks after Mike and Erin posted their anniversary walk, Mike invited me to his home in northeast Louisville to talk again about his missing daughter. Erin joined us, bringing along Luna as well as her youngest son, who tinkered with the decorative items shelved around the room. On the front of Erin’s T-shirt was a photo collage of Andrea, which matched the flyer on her screen door, which was also stapled to telephone poles on Fincastle. For two and a half hours, Erin and Mike detailed two years of false leads, difficult detectives, split family connections and hateful criticisms from strangers on the internet. We talked about the documentary, the continuous sparring with Nancy, and about the people who go missing in Northern Kentucky. We talked about the sad truth that while Andrea’s story has received attention, she is only one of many people who have gone missing.

“Let’s face the facts,” Mike says near the end of our interview. “This story would have not gone anywhere if Andrea had not looked for missing people.”

Could she really have just given up? Could Andrea truly be hiding in some arbitrary basement north of the Ohio River? Could she have torn herself away from her love for her two sons and just left? Or been pushed by family drama into suicide? Could she have been picked up by a random trafficker who managed — despite Andrea’s well-documented spitfire personality — to take her against her will, lock his doors and drive away into the night?

Mike says plainly from his chair, hands cupped together on his lap, “Every law enforcement person bar none has said she’s gone by now. She’s not alive.”

“I don’t want to accept that,” Erin says, across from him on the sofa.

“I don’t either, but — ”

“None of us do.”

Mike recalls one particular episode from the past two years. As they had with Andrea, the Leonards showed Mike the ropes at Loc8tors (how to do a grid search, how to do interviews), and they had him follow a tip about a hotel near a highway that might have been linked to his missing daughter. “I’m talking about a bad area,” Mike says. “Not good.” Mike drove there alone, hoping to pick up on some shadowy behavior, some tip that might help. He didn’t find any information about Andrea, but at 12:30 in the morning, a car pulled up. A girl of about 10 or 12 got out, and was dragged by a man. “Nothing a parent would do,” Mike says. He was “dragging her against her will.” Mike called 911. Another investigation was opened up. “But I don’t know what happened,” he says.

“Crazy, terrible things happen to vulnerable women,” Erin says. “It happens more than anybody realizes.” And, she adds, “I wouldn’t have realized any of this stuff if Andrea hadn’t gone missing.”

Mark Oprea is a journalist from Cleveland, Ohio. He has written for the Pacific Standard, Cleveland Magazine and Atlas Obscura.

Brendan Spiegel is the Editorial Director and co-founder of Narratively.