The roof garden terrace on the Hilton London Bankside. Photographer: Hollie Adams/Bloomberg

Honeybees, under threat in rural and agricultural areas, are finding an unlikely refuge: the big city.

The fuzzy pollinators, apis mellifera, have found new homes at places like the Beaugrenelle Commercial Center, one of Paris’s biggest indoor shopping complexes. Not far from the Eiffel Tower, the mall hosts a pesticide-free garden on its rooftop with Russian mint, Australian lemongrass, Indian holy basil and other plantings that attract local Michelin-starred chefs. The aromatic flowers and herbs also draw legions of bees that now live on a cleared corner of the roof overlooking the Seine River.

“It’s a heavenly buffet for them. They enjoy a healthy and varied diet, which makes the colony stronger,” beekeeper Diane Jenny said on a recent day as she checked the rooftop’s six hives, each containing about 40,000 bees, for potentially harmful parasites like mites. The bees were healthy and thriving, she proclaimed, and busy making rooftop honey.

The Paris initiative is one variation of a theme being pitched across the globe. For $500 to $3,000 annually per hive, urban beekeeping operations offer to install honeybee colonies on corporate or residential rooftops. The price includes regular checks on the bees’ health, perks like classes in biodiversity and beekeeping and, usually, samples of ultra-local honey. The companies also pitch loftier benefits — the prospect of providing pollination for urban plants and creating a hedge against widespread losses to bee populations, while also providing companies green credibility in exchange for a small investment and a bit of rooftop.

A beekeeper handles a hive frame on the rooftop garden of the Beaugrenelle Commercial Center in Paris. Source: Beaugrenelle

The business is buzzy, and growing. Apiterra, the urban beekeeping company responsible for the colonies on the Beaugrenelle rooftop, operates 300 hives across Paris, with clients including L’Oréal, AXA and the Paris Saint-Germain football club. Apiterra’s main competitor in Paris is Beeopic, which operates 350 hives, including at the Grand Palais exhibition hall, the headquarters of BNP Paribas SA, Europe's biggest bank, and luxury goods giant LVMH, and even some that survived the fire atop the Notre Dame Cathedral. All that activity is testament to Paris’s broader beekeeping upsurge: At the time of this writing in early 2022, there are currently 2,500 hives registered in Paris, up from 300 in 2010.

The growth isn’t limited to Paris. Beeopic was acquired in 2021 by the giant in the urban beekeeping world, Montréal-based Alvéole, which operates 3,100 beehives for 600 companies in 20 North American cities, including New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco and Toronto. Backed by Edō Capital, a venture-capital fund, Alvéole charges an average of $2,000 a year per hive, offering its corporate clients a package including candle-making courses and branded souvenir honey. The Beeopic tie-up gives Alvéole a European foothold that it says it will use to expand into London, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Brussels and Berlin.

“We want to enable corporations to have a bee-related project worldwide regardless of where their offices are located,” says Beeopic founder Nicolas Géant. He joined acquirer Alvéole as an operating partner, alongside three McGill University graduates who co-founded Alvéole in 2013. “Our aim isn’t to produce tons of honey, but to make companies and employees aware of the importance of bees in their daily life.”

Colony Collapse

It’s not difficult to make the case for bees. Out of the 100 crop species that provide 90% of food worldwide, 71 are pollinated by bees, according to a study by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization. And in many places, those bees have been imperiled by so-called colony collapse disorder, when most of a colony’s worker bees disappear. Over the last 15 years in the U.S., beekeepers have lost 28.3% of their colonies on average each winter, according to the Bee Informed Partnership, a nonprofit affiliated with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. That’s more than double the country’s 10% to 15% historical loss rates.

Although the disorder’s causes still aren’t fully understood, a landmark paper published in 2018 by University of Texas researchers pinpointed glyphosate, a chemical used in Roundup-type herbicides, as a potential factor. Roundup’s manufacturer, Bayer AG, has contested the study’s implications and has cited global food and environment regulators as saying that “glyphosate, when used as directed, does not cause unreasonable adverse effects on the environment.”

Against the backdrop of a dwindling bee population, scientists say that appropriately managed cities can provide the conditions that bolster bee health — abundance of pesticide-free, nectar-rich flowers on building rooftops, roundabouts, public gardens, balconies, even railway sidings. A study of 881 apiaries in and around the Paris metropolitan area found that urbanization has a positive effect on the winter survival of honeybee colonies. In return, honeybees can make urban landscapes greener, promote urban farming and bolster green roofs that building owners can use to earn credits toward sustainability certifications.

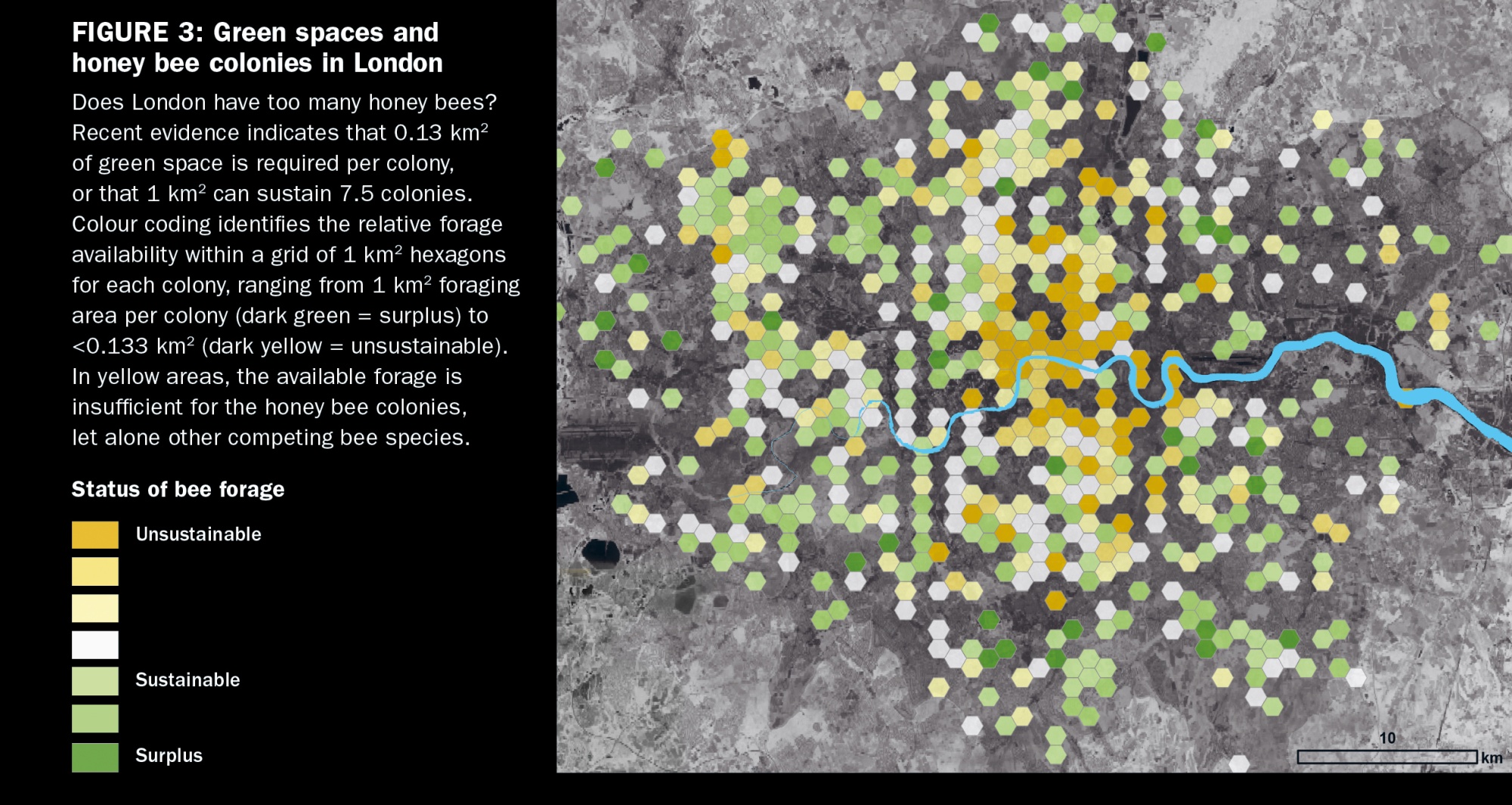

Some skepticism about urban bees are timeless, including allergic reactions to stings or the nuisance of bees drawn to al fresco dining spots. A more pressing concern for some experts: Corporate-led profusion of bees may not be sustainable. The quantity of available forage is dwindling in neighborhoods with beehive densities as high as 20 per square kilometer in Paris, London and Berlin. That leads to higher competition for food between honeybees and wild pollinators such as bumblebees, wild bees and butterflies. Because honeybees feed from a wider variety of flowers than most solitary bee and bumblebee species, their introduction can jeopardize native pollinators.

Beekeeper Dale Gibson, on the roof garden terrace at the Hilton London Bankside, warns against ‘beewashing’ — adding hives for green credibility without also bolstering plantings appropriate for urban pollinators.Photographer: Hollie Adams/Bloomberg

Dale Gibson, an apicultural consultant in Greater London, says his city has reached an unsustainable density of beehives — more than doubling in the last decade to 7,500, according to the U.K.’s National Bee Unit. Gibson says installing beehives as an image-booster without studying the impact on local plants and pollinators is a form of greenwashing. “Getting a ‘beewash’ effect is easy,” he said. “You just plunk a beehive on your roof and say, ‘That’s a great job I’ve done for biodiversity’.”

“Corporates have taken the urban beekeeping fad and turned it into an ecological disaster because they’ve gone ahead without considering forage scarcity,” he said.

Flower Offsets

Many large urban beekeeping firms are taking steps to compensate, at least in part, for their bees’ impact. Last year, Alvéole joined the 1% for the Planet movement, committing to annually donate a share of sales to nonprofits that plant wildflowers and support green projects. Several corporate clients of Alvéole, which include Goldman Sachs Asset Management and LVMH, and Google’s Toronto office, didn’t immediately provide comment. BNP Paribas’s real estate unit said it recommended its landscaper plant melliferous flowers, according to a representative.

Alvéole’s main competitor in the U.S., Boston-based The Best Bees Company, analyzes local honey in the 15 U.S. cities where it operates to determine the types and proportions of plant pollen in each. Then it can tell clients and local landscapers what to plant for all pollinators.

“What makes honey bees happy probably makes wild bees and other pollinators happy,” said Paige Mulhern, the company’s creative director. Mulhern said her company encouraged one of its big clients, commercial real estate firm Beacon Capital Partners — which says it has hives on 25 U.S. buildings, with plans to expand to 11 more this spring — to use their budget to invest in bee-friendly rooftop gardens.

A Londone forage map. Source: Phil Stevenson & Justin Moat, RBG Kew

In London, Gibson addresses potential imbalances using data and outreach. He says his Bermondsey Street Bees — which he runs with his wife, Sarah Wyndham Lewis — steers away from installing hives in bee-heavy areas. (They determine that by comparing a London forage map, provided by the Royal Botanic Gardens’ Kew Gardens, with a beehive-density and disease data set provided by the British government.) The company also asks companies that want hives to introduce foraging material, ideally within the hives’ four-kilometer flying range. Clients can satisfy the request with rooftop plantings. Or, they can fund local greening organizations that have already scouted out planting spaces and the nectar-rich species that will work there.

Urban Wilding

The bee-friendly efforts are one part of a broader push to bolster plantings and set aside wild spaces in urban areas across the world. The Netherlands has championed city greening, with residents replacing garden and walkway tiles with bushes and trees. In 2019, the city of Utrecht transformed its 316 bus stops, turning the shelter roofs into boxes planted with pollinator-friendly sedum, a low-maintenance plant that resists dry spells. Designed to meet the code of best practice set by the U.K.-based Green Roof Organisation, these “bee bus stops” also capture fine dust and conserve rainfall. Similar stops are now being built in Leicester, in the U.K., as part of the city’s “Bee Roads” program.

Other bee-embracing cities include Singapore and Ljubljana, Slovenia, which have developed bee paths — like a wine trail, but with attractions that feature “bee hotels” and diverse bee-attracting gardens for the public to view bees up close. In Santiago, Chile, former history teacher Felipe Bastías operates 80 urban beehives that provide the star ingredient in a blonde ale produced by a local brewery. Bastías says he steers some of his honey profits into his program to teach underprivileged local kindergarteners about beekeeping and, by extension, how the natural world can play a role in urban life.

A bee-friendly bus stop in Utrecht, Netherlands. Photographer: Barbra Verbij/Gemeente Utrecht

Then there’s a more prosaic question: How’s the honey?

Remarkably, it may be purer than the countryside version. Honey produced in rural and agricultural areas can bear dangerous amounts of glyphosate, according to several studies, even as other studies have found urban honey safe for consumption.

That distinction was borne out in an unusual experiment in Uruguay. As part of a project launched last year called miel de hormigón — honey from concrete — France’s embassy in Montevideo partnered with the Uruguayan Apicultural Society to compare honey from the center of the capital with honey from the rural suburbs. There were traces of glyphosate in honey produced at the French ambassador’s residence in Montevideo’s outskirts, but none in the one produced on the roof of the French embassy in the city’s center, according to an unpublished lab report delivered by the Technological Laboratory of Uruguay, which was reviewed by CityLab.

“We have won our bet to show that urban honey is less polluted than suburban honey,” said François-Justin Brivot, cooperation officer at the Embassy of France in Montevideo.

Complex Taste

As to taste, city honey can have a more diverse floral composition than rural honey if bees have enough foraging spots, says Gibson. That, he says, can provide a more complex taste. Some London honeys are described as citrusy, while the two specialties of Berlin are acacia and linden.

But because honey is so local and seasonal, it can be hard to generalize, says Carla Marina Marchese. An educator and the co-author of Honey for Dummies, she’s accredited by the Italian National Register of Experts in the Sensory Analysis of Honey — in short, a honey sommelier.

“Much like wine, honey is directly reflective of a local terroir. Every city, and every area within a city, has a very specific sensory profile,” Marchese says. “You can plant lavender trees in New York City, but the honey you will get is never going to taste like the true lavender honey from the Mediterranean.”

“There’s a lot of other city plants. There’s pollution,” she adds. “It’s a very different terroir than the Mediterranean.”

In Paris, a few floors below the Beaugrenelle rooftop, mall shoppers can buy 150-gram containers of the honey for 10 euros ($11.30). A sensory evaluation report — which the beekeepers commissioned from a lab that has government accreditation to analyze honey — characterized it as “woody, floral, minty and slightly exotic.” A receptionist at Beaugrenelle, Yasmina Guettaia, offered a more concise review of the jar she received for her birthday. “It was very sweet,” she said.

(Corrects spelling of beekeeper’s surname in third paragraph. A previous version of this article corrected spelling of Carla Marina Marchese's name and the source of her honey sommelier accreditation.)