On October, 8 1982, Mom wrote in her diary that she slept until noon that day and woke up feeling refreshed, filled with a renewed sense of hope. She had an appointment with her psychologist that afternoon, so she grabbed her toilet kit and headed for the common bathroom in the hotel where she’d taken up residency after life on the streets.

When she walked in and she saw a big, bald, completely nude man standing in front of a mirror. His muscles, covered in prison tattoos, rippled as he brushed his teeth, while his penis swung back and forth to match the rhythm. Unfazed by Peggy’s sudden appearance behind him, the 6-foot-2-inch man simply continued his brushing. Frozen in her stance, Mom, who looked like a young Mary Tyler Moore, couldn’t take her eyes off him. When he lowered his brushing arm, she could see the words “BAD BOY” written across his chest. At least, that was how the homemade tattoo read in the mirror. He must have etched it into his skin while using a mirror as a guide, because when he turned around, straight on it read, “YOB DAB.” With a mouthful of toothpaste, he barked, “Fuck you lookin’ at?”

“Nothing,” said Mom, sounding like a mouse.

“So I’m nothin’, huh bitch? Get yo’ ass out dis mothafuckin’ toilet till I’m finished.”

He didn’t have to tell Mom twice.

Back in her room, she realized she was going to have to see Dr. Leibowitz without showering. Afraid to go back into the bathroom, she snuck into the fire emergency stairwell and urinated on the floor. She was midstream when she realized a man in a business suit was only a few feet from her, receiving a silent hand job from one of the hotel’s cross-dressing residents. She finished peeing and left without them noticing her.

That night, after her doctor’s appointment and a shift at work, Mom was sitting on the stoop at the front of the hotel, smoking a cigarette, when “Bad Boy,” the man from the bathroom, came out the front door. Mom was still afraid of him, but she tried not to show it when he asked for a cigarette. She shook a Lucky out of the pack and held it out for him. He thanked her and lit a match with his thumbnail. “Was you the one came in seeing me brushin’ this mornin’?” he asked. Mom nodded yes. “Sorry ’bout that. I was, like, in a bad mood.” He finished his cigarette and tossed it on the ground. “I was tired this morning,” he said, as a way of further apologizing. He added that if Mom had any problems with anyone, here at the hotel or anywhere else, she should come to him and he would take care of it. His name was Carter, Mom would soon learn. He was 28 and had spent more than half his life in the juvenile or prison systems. His specialty was robbing drug dealers because they always carried lots of cash. He was the first of many friends Mom would make at the Jane West Hotel.

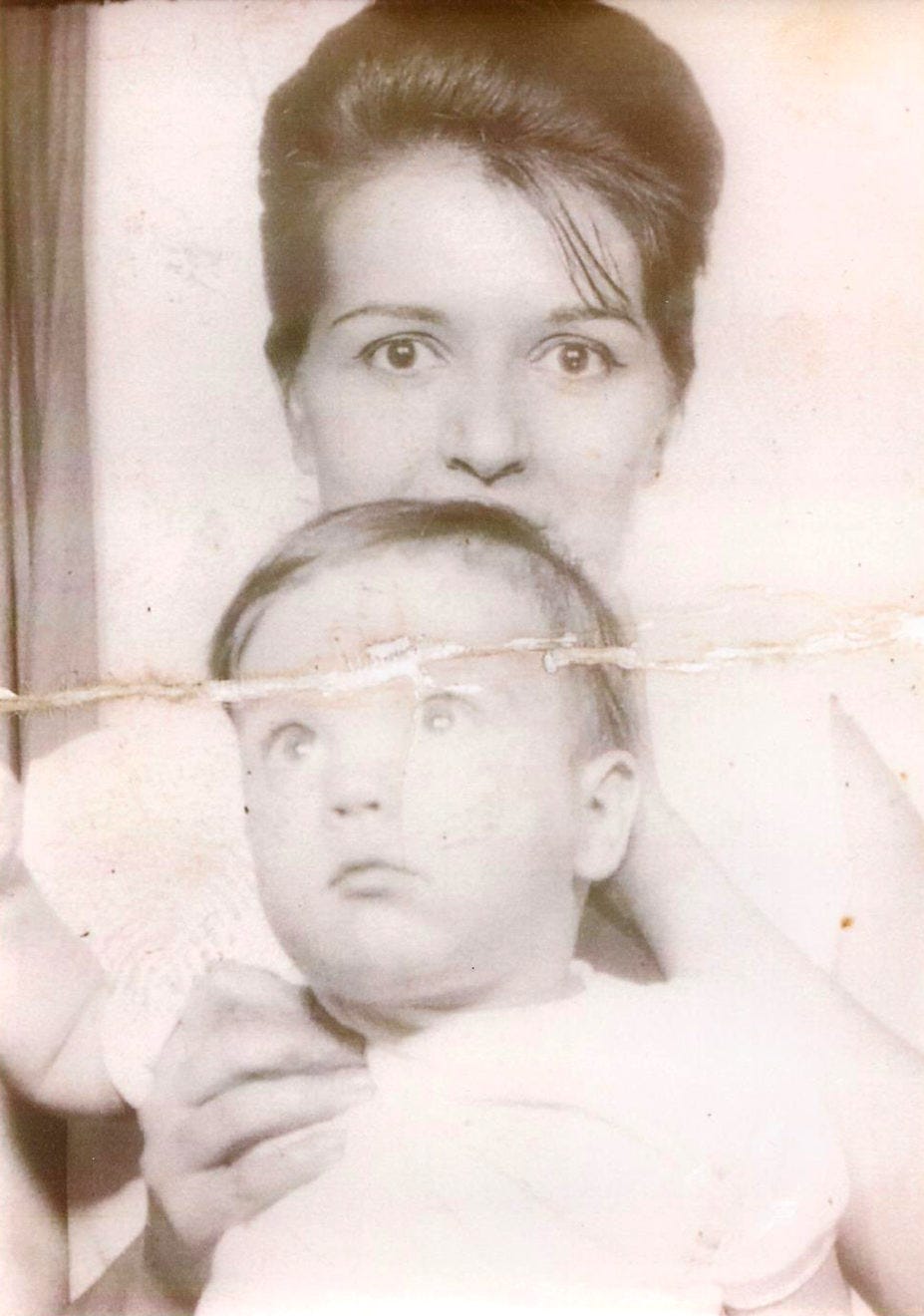

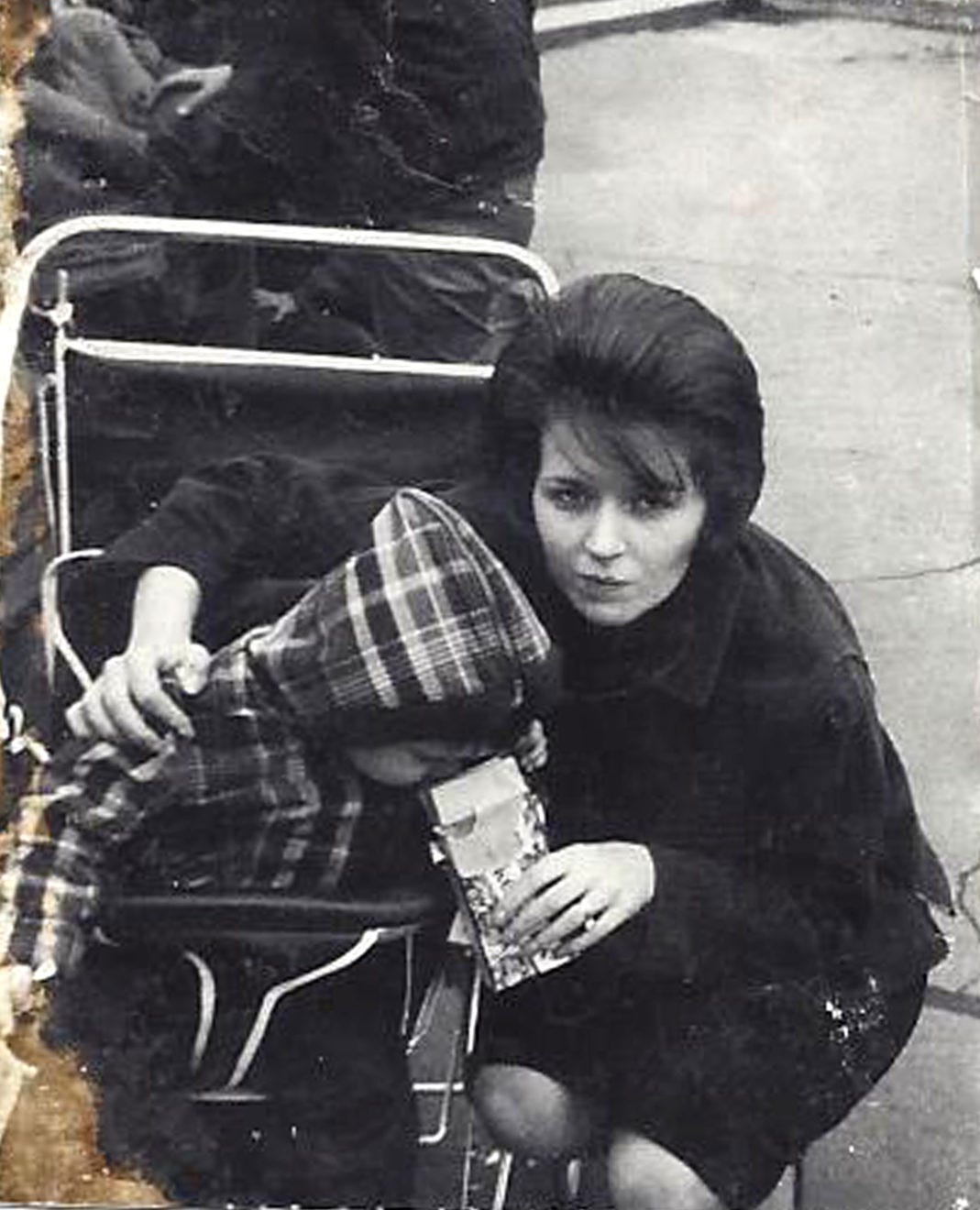

My mother, Margaret “Peggy” Hannity, was born on July 14, 1946, in Harlem, the daughter of an Irish Catholic construction worker who drank almost as much as he worked and a Scottish woman who moved to New York City as soon as she was able, eager to soak up the bright lights of the legendary big city. Jack drank away most of what he earned, so Beatrice worked full-time too, leaving Peggy to help out with her two younger siblings’ homework, as well as packing their lunches and getting them off to school.

Peggy graduated high school with an A average, then took secretarial and nursing courses at community college while waitressing in a theater district diner on weekends. I think that was the beginning of her troubles. Soon she was hanging out backstage with her actor friends after shows. This was her first introduction to social drinking, which I guess should have set off warning lights for her. But like her mother, she was attracted to the glamour.

Her partying days didn’t last long. In 1964, at the age of 19, Mom found out she was pregnant. The boy who’d knocked her up, a good-looking mechanic named Robert Hayden, “did the right thing” and married her. They spent their wedding reception at McSorley’s, an Irish alehouse in the East Village famous for its sawdust-covered floors, and found a two-bedroom in Upper Manhattan, where I was born in the summer of ’64.

Mom got a job as a secretary on Wall Street, but her drinking only got worse, and by ’68 Dad walked out. No longer able to afford the apartment, she moved us all back in with her mother. Grandpa Jack was gone too, having left one evening to buy cigarettes and never returning. With her mother and sister as built-in babysitters, Mom partied with her friends more and more, spending less and less time at home with me.

In 1970 she met Joe, a bond trader and rising star at the firm where she worked. They dated for about a year, married in a civil ceremony, and we moved to a pricey apartment in Brooklyn. Mom quit her job at the brokerage house, but instead of staying home playing house, she kept going into the city to meet friends, eat, drink and smoke weed. She often came home late at night, and the babysitting fell to Joe’s parents. He pleaded with her to see a psychologist, or find a clinic where she could try to get a handle on her drinking. Mom went ballistic, and that was the end of Joe.

It was the summer of ‘78. I was 14 and it was moving time again, this time far down the social ladder to a flat in the rough-and-tough Red Hook section of Brooklyn. Mom moved in with Kevin, a guy she knew from an old job. I don’t remember much about him, except that I couldn’t understand why Mom was with him. There was only one bed, so I slept on a comforter on the floor. Eventually, I packed up my few belongings and moved back in with my grandmother in Manhattan.

One night in February of 1982, while Mom was out God knows where, Kevin got together with a few of his buddies and moved all his belongings out of the apartment. Alone in the apartment with no furniture, no electricity, and no way to pay the rent, Mom didn’t know where to go or what to do. Then a sheriff and his crew came and evicted her, leaving her alone on the street with only a garbage bag of belongings. At that point, she’d had so many clashes with my grandmother that she would rather do anything than swallow her pride and call her to ask for help.

There was nowhere to go but down.

Mom found a women’s shelter, and during her first, fearful night sleeping on a cot, she held her belongings close and didn’t even take off her shoes. Even so, in the middle of the night another woman stole them right off her feet.

The next morning, Mom picked up her single garbage bag of belongings and walked out of the shelter barefoot, then into the first subway entrance she came upon. For the next year she lived in the subways, watching people go to and from work, imagining their lives then curling up in the recesses of a station for a peaceful sleep. She began to explore the bowels of the system, unused tunnels that were occupied by a community of cast-aside characters. One day she walked by a teenage girl wearing Mickey Mouse ears, lying back, shooting heroin; an older man masturbating, holding a tattered Playboy magazine; a screaming woman who thought Mom was attempting to pick up her boyfriend because she had innocently stepped over the sleeping man. Mom quickly learned to keep moving in order to stay out of harm’s way. She rode the trains for hours at a time, going back and forth and nowhere, daydreaming about how to get back to a decent life. She always carried an aluminum thermos of water under her coat, tied to a rope, filling it from leaky fire hydrants and also using it as a weapon on several occasions. Most times one swing did the trick, enough to scare off unwanted company.

She spoke once with a field worker from the New York City Department of Homeless Services, who offered her a decent meal, medical services, even a roof over her head. She was tempted, but a pair of sneakers she found in the subway were still the only shoes she had, and the idea of going back to a shelter and having them stolen was something she couldn’t deal with. Thanks, she told them, but uh-uh, no thanks.

Then one frightening encounter changed everything. It happened on a rainy night in Upper Manhattan. Mom was in an exceptionally filthy subway bathroom at an elevated station, using a trickling faucet to wash out her underwear. The toilet stalls didn’t have doors, and one was occupied by a woman using her shopping cart filled with junk to give herself some privacy. All of a sudden, a man ran into the bathroom, his eyes wide and crazy. When he saw Mom, he pulled a large steak knife from his inside coat pocket.

“Your ass is my ass tonight, bitch.” He stared at her as he opened his fly with his free hand. When he was exposed, he approached Mom, who pulled her coat tight around herself as a shield. At the last minute, when she could see the yellows of his spotted eyes, she swung her thermos, knocking the knife out of his hand, followed by a swift kick to his groin. He grabbed her hair and pulled her down to the cold tile floor. Mom screamed at the top of her lungs as he positioned himself out on top of her.

Suddenly, he jerked up and screamed, swearing in Spanish. Mom could see blood everywhere as he rolled off of her, She had no idea what, or whom, had saved her, until she saw the woman from the other stall standing over him, her pants still around her ankles, a long Japanese sword in one hand, tinted the color of dark blood. (To be honest, I was initially somewhat skeptical about this part of her story myself. But years later, as a cop, I ran into a homeless woman in the Staten Island Ferry terminal who also had a sword in a shopping cart. This encounter convinced me that Mom was on the level with her own sword story. Needless to say, I tossed the weapon in the river.)

Not knowing or caring if the guy was dead, Mom grabbed her wet underwear and rushed out of the restroom. She knew it was time to reconsider letting the city help her find safe housing. As soon as she spotted the omnipresent outreach van, she went up to the window and asked if there was anywhere she could stay. The social worker had one voucher left, for an S.R.O. (single room occupancy) — the Jane West Hotel, located in the wild west fringe of the West Village. Mom knew that this was a last-stop flophouse. S.R.O.s are buildings where small rooms, typically with no private kitchens or bathrooms, are rented out; in 1980s New York there were many such S.R.O.s, usually for low-income and formerly homeless people, and often in derelict conditions. But it was a roof over her head, one that was free, private and relatively safe. She thanked the fellow as she entered the van for the quick ride to the Village, about to pass through the gates of her next adventure.

The six-story, red-brick building that housed the Jane West Hotel, at the corner of Jane and West streets, seemed to be in good structural shape for its age, faded and grimy as it was, like a warrior after a battle, worn down but still standing. A majestic cupola sat atop it like a crown, and a three-foot black wrought-iron fence surrounded the building, giving the hotel a feel more like a fortress than a flophouse.

The social worker escorted Mom up the front steps and into the huge lobby area, which had the heft and feel of a small arena. Mom sensed this place had a colorful history. In the 1930s it was the “Seaman’s Retreat Center,” a resting place for sailors. A faded lobby plaque told her that the surviving passengers of the Titanic had stayed there in 1912. The social worker gave mom a list of phone numbers for benefits and a couple of subway tokens so she could report to the nearest social services office as soon as she was settled in.

“Good luck,” he said, then shook Mom’s hand and left.

The desk clerk, Charlie — Chicky to everyone at the Jane West Hotel — came out of the back room. A World War II Navy veteran and one-time amateur boxer, Chicky had seen better days. He didn’t say a word as he slipped her key through the opening at the bottom of the metal cage screen atop the desk (like something one would see in an old train station) and pointed to a sign on the wall:

NO VISITORS PERMITTED AFTER 8 P.M. —

ABSOLUTELY NO OVERNIGHT GUESTS!!!

“If you flat back or peddle ass in this place, I get a taste of the take,” Chicky commanded. “Got it, sweetie?”

Mom blushed, then nodded her head quickly. When she finally found her voice, she said, softly but firmly, “I’m not a pro or a whore, or whatever perverted thing you may think, sir. Watch your tone with me, otherwise we’ll have a problem. Got it, sweetie?”

They looked at each other for a couple of seconds, like two boxers in a ring, before Chicky smiled and said, “You’re OK, kid. I’m Chicky.” He motioned for the sleepy security guard to escort Mom up to her room. The residents knew him as Clifford, but they sometimes called him Bigfoot because of his girth. Standing at an imposing 6 feet 5 inches, he always wore suspenders and had a dime-store police badge pinned to one of the straps. He introduced himself to Mom, carried her garbage bag of belongings over to the elevator like it was a designer handbag, and instructed Richie, the uniformed elevator operator, to take them up to Room 412. (Quick note: I have used pseudonyms for Richie and some of the other people in this story, in cases where I recall the person but don’t remember their name. All of the events described in this piece are real, however; they come from Mom’s diaries and notes, stories she told to me, or my own memory; in some places, I’ve recreated specific scenes and dialogue as best I could.)

When she opened the door to her room, she saw a metal bedframe and a mattress, a small dresser, and two tilted shelves hanging precariously on the wall. The recessed window looked out into a shaftway. For a window curtain, the previous tenant had hung a sheet.

Mom headed to the common bathroom and took her first hot shower in she couldn’t remember how long. The warm water invigorated her, and as she toweled off, she began to think, How the hell did I get to this place in my life? She thought about me, for the first time, really, since she’d been put out on the street. She decided to give me a call from the lobby payphone when she was dressed, to let me know she was OK. I was still living with Beatrice, my grandmother, who handed me the receiver after a few words with her daughter. I offered to come see Mom, but she said no, she wasn’t ready. I wanted to tell her about passing the high school equivalency diploma test, about working in an auto body shop during the day, and evenings stocking shelves at a supermarket. But the whole call lasted just three minutes. Mom said she would call back in a day or two, then hung up.

I heard the click and put my head in both of my hands.

Mom managed to get a job answering phones at a nearby Chinese restaurant, and she used the small amount of extra cash she made to decorate her room. She added window curtains and, with Bigfoot’s help, hung a new shelf and placed a porcelain Statue of Liberty figurine on it. The final touch was mounting a crucifix on the inside of her door. She began calling me from the lobby payphone once a week, and she also started to hang around the S.R.O.’s threadbare lounge, which is where she met Emilio.

Emilio had short, dark hair and always wore a dark sweat suit — except when he went to the common bathroom and changed into a skintight red miniskirt and matching wig. He was in his 20s, young enough to look good as a man or woman, and he used that to his advantage at nights, when he picked up clients in the nearby Meatpacking District. He and Mom clicked. She found him interesting, creative, perhaps even artistic, like her old theater friends. Emilio invited her up to his room to show her his wardrobe. While there, he offered her a beer. It had been several months since she’d had a drink, but she couldn’t resist. After her third one, she was laughing and talking to Emilio like they were old friends. He rolled a joint and soon they were both high, giggling like two teenage girls.

From a very young age, Mom had always liked the world of fashion, and there was a time, another life ago, when she thought she might become a clothing designer. Now she started helping Emilio create his working outfits, which he modeled for her in full drag. The new friendship reinvigorated her, but it was also dangerous. One day, after assisting Emilio with his wardrobe planning, Mom stumbled back to her room and passed out drunk on the bed.

At Christmastime, Mom added Jägermeister, Bailey’s Irish Crème and Mint Schnapps to her well-stocked liquor cabinet, and was even able to convince Chicky to cough up money for an artificial Christmas tree to put in the lobby, along with a menorah in case any of the residents were Jewish. She, Emilio and two of his friends, Gordon and Gary, put up the tree decorations, which consisted of colorful socks, cut-up beer cans, condoms and rolling papers. To top it off, Mom got up on a stepladder as the guys held it steady so she could attach an elaborate star she’d made out of aluminum foil.

Gordon and Gary, a.k.a. the G&G brothers, were in their early 20s, both gay. They looked, dressed and acted alike. Clean-shaven with neatly combed hair, they could have passed for a couple of college seniors. The G&G brothers loved to sing and had dreams of becoming a professional duo. They spent a lot of their time in the hallways, belting through the entire soundtrack of Saturday Night Fever and the hot new Broadway musical Cats.

But they weren’t the top showbiz talent at the S.R.O. That title went to a young Black man by the name of RuPaul. Mom could see immediately that he had the voice, charisma and presence to be a big performer one day. RuPaul lived in the hotel’s large cupola, the fortified brick turret at the top of the building, along with two other men; one looked like Freddie Mercury and was almost always shirtless, showing off his perfect abs. They were quite the trio, often the center of social activities. There’s a video of the three of them cavorting around the hotel on YouTube.

The S.R.O’s ballroom had been converted to a theater not long before Mom arrived, and RuPaul would perform there in drag. Some notable shows even made their debut there years later, most notably Hedwig and the Angry Inch, a musical centered around a genderqueer rock singer, in 1998. (Years later, the now-famous RuPaul reminisced to the New York Post, “when I did have money, I would rent a room at the Jane West Hotel — when I was getting some go-go dancing gigs or I could perform to my own songs. It was a dump. It had that distinctive New York smell — it’s like a mixture of mold, soot and grime. The only place you can smell that now is in the subway.”)

Another resident, Wanda, was a short, heavyset 30-year-old woman with a flair for the dramatic. That Christmas, she got drunk and high and wandered the hotel wearing nothing but a Santa hat and a garland wrapped around her. She banged on every door until the occupant opened, then belted out Christmas carols.

There was always something going on at the S.R.O. One winter night Mom stopped onto the third floor, which had a reputation for being the partying floor, mostly because of its younger tenants. They would leave their doors wide open and go from room to room like they were in a college dorm, drinking beer and dreaming up merriment. As Mom peeked her head in the third-floor stairwell door this evening, she saw two lengths of fire hose running parallel to one another along the floor. At one end of the hose were a dozen beer bottles, set up like bowling pins. At the other end was Diamond, a beautiful young blonde she’d met in the lounge a few weeks earlier, who spent most nights working as a call girl. Diamond was crouching while holding a large, bowling ball–sized wad of aluminum foil, while a crowd lined the makeshift bowling lane, cheering her on. She turned around and told my mom, “I come out the bathroom and they ask me to roll this big thing of, whatever. But really, I think they just want to see my boobs flop out my bathrobe.” She turned back around and rolled a strike, then gave Mom a tipsy high five.

From our conversations, I could sense she was bonding with several of the other residents, probably because many of their plights were similar to hers. They shared food and drink and hung out all the time. I guess they leaned on each other for support. But while Mom was spreading holiday cheer around the hotel, she was still hurting on the inside. I could tell, because she called me several times, still refusing to tell me where she was because she didn’t want me to visit. But we had long talks and she went into details about the people she lived with. I knew in my heart that she was partying again. That was the reason why she didn’t want to see me.

Mom spent much of the winter hanging with her new friends at the hotel, getting drunk or high, wasting her time and her life away, getting fired from her job at the restaurant. She didn’t care; she was sick of Chinese food anyway. Instead, she became the S.R.O.’s resident mentor. She hung out in the lounge, where her favorite seat was an elaborate, faux Louis XV chair where she would perch and fawn over her subjects. She exuded relative class and charm, and dispensed interesting commentary to anyone who would listen: gay, straight, young, old, Black, white — the S.R.O. was filled with every type of person, and Mom loved talking to anyone and everyone.

The residents soon sought her advice on everything from family matters to fashion (she especially loved helping all of the cross-dressing residents with their outfits), education, business (Emilio asked her advice on whether he could write off breast implants as a business expense) and job-hunting skills (she was a fantastic typist and volunteered to help other residents type up their resumes). There was even a young woman, Terri, no more than 20, whom Mom helped learn to read and write after she saw her in the lounge one day, struggling to sound out words in the newspaper. Mom had certainly fallen far, but she had more of an education than most at the S.R.O. and she was proud to be able to offer them the skills that she had. She was good at this, helping. If only she could do the same for herself, she told herself, over and over.

Springtime sunshine brightened up my mom’s world, and she found a new job as a part-time waitress at a nearby Greek diner. The extra money meant she could get a phone in her room and would no longer have to use the one in the lobby. As soon as word got out she was working at the diner, Emilio and Bigfoot came around, looking for freebies. She did what she could, under the watchful eye of the owner, Spiro. She quickly developed her own steady regulars, mostly businessmen who liked her so much they often made passes in the form of job offers. She always wrote down their numbers or took their cards — said she would think about it. Not really though. She was now somewhat content with the rung of the ladder she had managed to climb to. She was scared that if she tried to skip too many steps, she was likely to fall flat on her pretty face again.

While serving a stack of pancakes to customers in one of the booths, Mom got a creepy feeling that she was being watched. Not by Spiro, who was always making sure she put all the cash into the register, but someone else.

On the way back from the booth, she saw me sitting at the end of the counter.

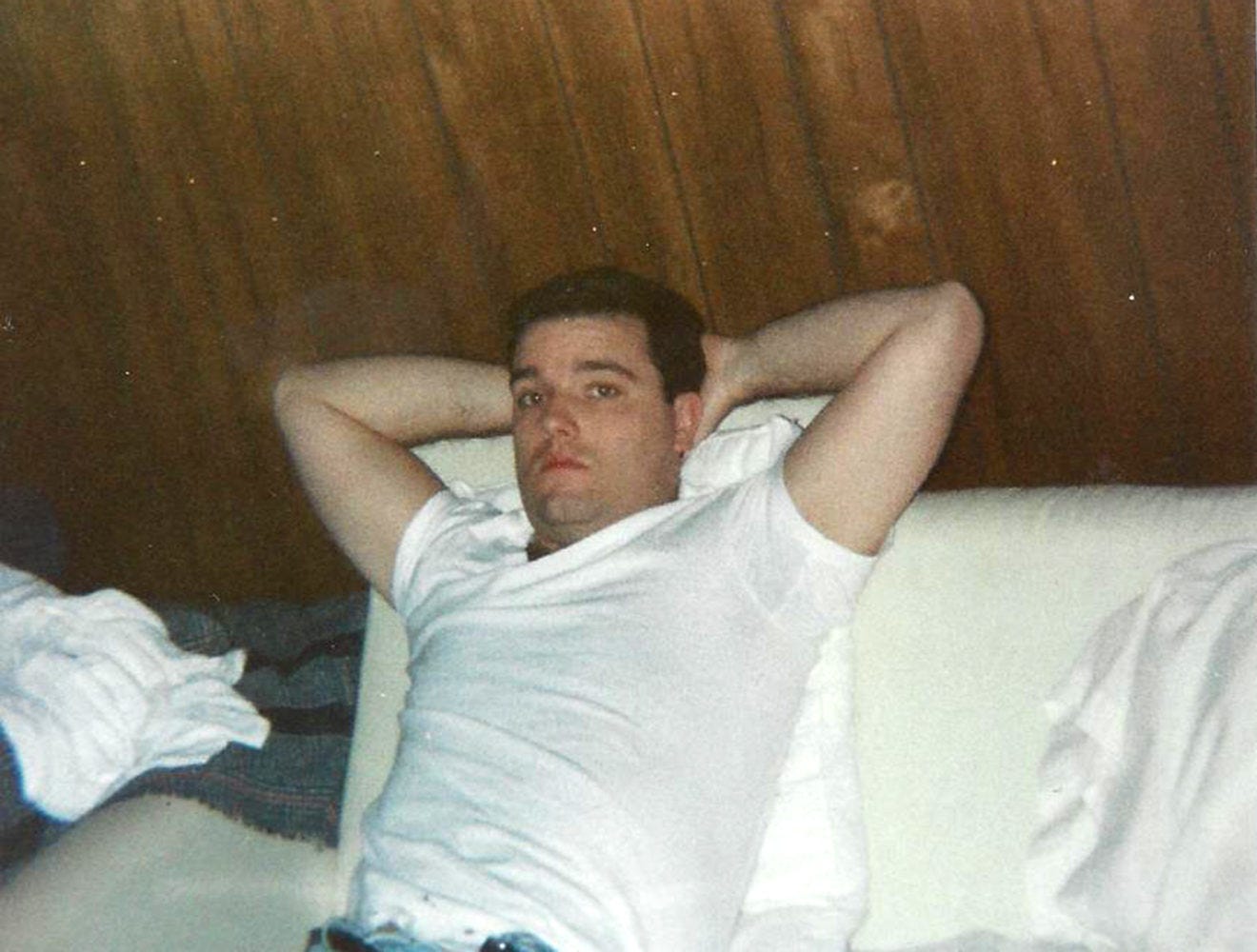

Mom walked over, slowly at first, afraid to believe it was true. It had been nearly two years. I was 17 now. Finally, she smiled and asked how I found her. On her break, we walked over to the Hudson River. With the slow-moving boat traffic as background to our conversation, I explained that one of the messengers at the Wall Street firm where I was working was a childhood friend of mine who remembered her. He casually told me he’d once seen her sitting on the steps of the S.R.O. smoking a cigarette while talking to “some weird chick.” I decided to visit, where I met Clifford, a.k.a. Bigfoot, who directed me to the diner.

As a tug pushing a barge floated silently by, she asked, “How is everyone doing?”

“Everyone is fine, Mom.” I hadn’t said “Mom” in such a long time. It felt kind of good, normal.

“Oh, that’s good,” she said cheerfully.

“I got my high school equivalency diploma last year.”

Mom smiled. “Congratulations.”

We talked for a while, but we both felt awkward. I asked if I could see her apartment, but she wasn’t ready for that and made up an excuse about why I couldn’t. On the train back uptown, I felt a hard sadness. I wanted to rescue her, to take her out of that shithole, but she actually seemed to like being there. My heart was both hardened and broken. Back in her room, her own waterfall of emotions cascaded down. She was thrilled to see me and was glad I was all right, yet somehow she felt I had pierced the delicate world she had created for herself. Her survival mechanism had been exposed, and she was embarrassed I had seen her this way.

For the next several months, I would stop by the S.R.O. unannounced to check up on Mom, to tell her how concerned I was about her. She always waved me off as being paranoid and told me to toughen up, that life wasn’t always pretty or perfect. Our visits often ended in loud arguments. She denied using drugs; I knew she was lying. She had, in fact, begun experimenting with pills, and I demanded to know where she was getting them.

It took me a while to find out who the pusher was. One night in 1984, I stopped by to see her unannounced, and that’s when Bigfoot got a hold of me. Wearing that stupid dime-store police badge on his suspenders, he sidled right up with an I have to talk to you look on his face. I was surprised when he said he respected me for trying to talk some sense into my mother. He looked around to see if anyone else was watching, then told me, “The guy you want is Miguel. He lives in Room 441, and you didn’t get this from me.”

I went to Room 441 and knocked aggressively. When I told Miguel I was Peggy’s son, he became very friendly and asked me to come in, to have a beer with him, which I graciously declined. I stood in the doorway, measuring my words, calmly telling him to stop supplying my mother with drugs because they were hurting her rehabilitation. He instantly did a 180.

“Your mother gets what she wants from me because it makes her feel good,” he said. “That’s the way it is, man.” He lifted his shirt to reveal a knife tucked into his waistband. That was enough for me. I thrust a clenched fist into his jaw with such force that he stumbled backward and collapsed on the bed. After a few seconds, he got up slowly, dazed, and tried to pull his knife out. Before he could, I delivered a flurry of punches and he flopped to the floor, his face covered in blood. I leaned over and told him if he ever supplied my mother with drugs again, I would put him in the hospital for a very long time.

As I closed the door behind me, I saw Mom standing in front of her room. She cowered slightly as I walked past. I turned to her and smiled. “What are you worried about? I just saved your life, so toughen up.”

Someone had heard the commotion and called 911. Miguel didn’t talk to the cops about who beat him up, but they did notice a large amount of drugs on his night table, enough to arrest him for felony possession with intent to distribute. I heard that after being treated at the hospital, he was released into custody and eventually sent back to prison for violating the terms of his parole. I never saw him again. As far as I know, neither did Mom.

Mom was always bouncing between jobs, and like most everyone at the hotel, never sure where her next dollar was going to come from. One day, James, a fellow resident, asked her for a favor. “Would you be interested in walking some dogs for me this Friday afternoon?” he said. “I have a very important meeting I have to attend.” It quickly became clear that he had no ownership connection to the dogs. People paid him to walk their dogs twice a day. He said he would pay her to cover him for one afternoon.

“How many dogs are we now talking about?” Mom asked.

“Only six,” James said.

“OK, I’ll do it.”

Friday morning, James came to Peggy’s room with the keys, addresses and apartment numbers of each dog. “Pick them up around 4 o’clock, walk them along the piers, let them do their business, and bring them home. It should take no more than an hour.” She did just as he said, walking them as one group of six, three on each hand. The dogs were well behaved. It was a simple job and a fast payday. Until, that is, she got back to the building and ran into an unexpected problem. She could not remember which apartment was associated with which dog. She had the paper with the apartment numbers and dog’s names, but nothing describing their breeds and colors. She tried calling out each dog’s name, but it didn’t work. Because Mom never owned a dog, she didn’t think to look at their collars, where five of the six had tags with their names. In her panic, she took her best guess and returned the dogs to what she thought were the correct apartments.

The next morning, an angry James came to her room to pick up the keys, and Mom knew what he was going to say; she had put all six dogs in the wrong apartments. James said one lady nearly fainted when she got home to discover her cairn terrier had become an English sheepdog. Mom thought this was kind of funny but didn’t dare laugh.

One Saturday morning, Mom was up early to go grocery shopping. When she returned to the hotel, Bigfoot helped carry her groceries up the stairs and to her room, then back down as he said he had something to show her. She had a funny feeling he was up to something. Emilio, too, was acting strange. And then, when she turned the corner to enter the lounge, people inside erupted with a unified belt of “Surprise!”

Mom was stunned as Emilio, Gordon, Gary and several others were standing under a colorful, crayon-scrawled banner that read “HAPPY BELATED OR EARLY BIRTHDAY, PEGGY.” She couldn’t believe they had put this together. The artistic value of the banner was like something seen in grade school, but it was the thought that counted — not the fact that no one actually knew when her birthday was.

“You’re always helping others and so we figured, what the heck?” Emilio said, smiling. Mom giggled as they brought out a small sheet cake, a couple of six-packs of Miller High Life, and one-gallon jugs of Hawaiian Punch fruit drink. Mom spent the rest of the afternoon in the lounge, drinking. She was in her favorite setting: friends and booze.

The party had a deleterious effect on Mom. She started drinking more heavily in the days after, into the night, and would wake with a hangover that ruined her mornings, and often afternoons too. Over the next several weeks, whenever I’d stop in to see her or call, Mom’s personality would change in an instant, triggered by my words, or just by someone coming into the lounge, even a light turned on or off. One minute she was calm, and the next, belligerent and vulgar. I wasn’t sure how to handle it. An added concern was that at the time I was being investigated by the New York Police Department’s recruitment division because I was applying to be a police officer. I kept this from Mom out of fear she’d attempt to sabotage the process. She once told me she’d say or do anything to prevent me from becoming a cop. I think it was a combination of fear for my safety and disdain for authority figures. In my head, I thought I was doing it for just one reason: to help people. But now I know there was another, more subconscious motivation for my career choice — my failure to save my mother, to save her from her most dangerous enemy, herself.

Mom continued to serve as both unofficial mentor and life of the party at the S.R.O. When she was relatively sober, she continued to tutor Terri, whose reading skills were becoming markedly better. It was not unusual for Mom to spend most of the day with her — until the drinking started, anyway.

On Halloween one year, Mom watched the parade along Sixth Avenue in the Village. She hid two beers in her purse, taking swigs when the cops were not facing her. She left before the parade ended. Back on top of the S.R.O. at the rooftop “bar,” things were lively and familiar, especially with her arrival.

“The Queen of the S.R.O. is here, you mothafuckas,” she announced with a cocky tone, setting down a six-pack of Schlitz on the parapet, in front of the usual collection of misfits.

Mom kept drinking after everyone else left, sitting and staring at the twinkling skyscraper lights. It was after 2 a.m., and for some reason the depressing truth of her situation crept up on her. She began to weep loudly, not realizing her wails could be heard from residents in neighboring buildings. One of those residents called the S.R.O.’s front desk to complain about the noise. Chicky went up to see who it was, discovering Mom pacing, ranting, with a wild look in her eyes. Fearing she might harm herself, he went back down to the lobby to call 911.

Luckily, I had been at a party nearby, on Bleecker Street. I’d recently been accepted into the NYPD and was well into my probation period at the police academy. I’d mostly avoided seeing her lately as I wanted to stay far away from anything that could jeopardize my new career. I’m not sure why, intuition perhaps, but that night a voice in my head told me to stop by. When I walked past the front desk, Chicky said, matter-of-factly, “Hey kid, ya better get up to the roof. Ya mother’s up there, freakin’ the fuck out. Already called the nut job squad.”

In a panic, I ran up the six flights to the roof. She was crouched near the edge of the roof, sobbing. When she realized I was there, only a few feet away, she quickly turned to look over the edge. The parapet could not have been more than three feet high, so if she decided to jump, it would have only required simply leaning over. I lunged, grabbing her arm, and pulled her tightly into me. We sat on the tarred surface of the roof, and I would not let go while she and I cried together. Thirty seconds later, several police officers appeared, quickly followed by two paramedics. She paused her sobbing long enough to tell us she was all right and just needed a good cry. One of the paramedics said it was the protocol to take her to Bellevue Hospital for a psychological examination. Mom didn’t resist, and I put my arm around her as we walked down the stairway to the ground floor. After a stay in the emergency room, Mom convinced the doctors that she wasn’t a danger to herself or others, and made her way back to the S.R.O. I don’t know why — she wrote nothing about that night in her diary — but Mom concluded the entire episode on the roof was my fault. The next time we spoke, it wasn’t much of a conversation, really, just Mom ranting and yelling, then hanging up on me.

I felt it was best to just let her vent. Hopefully, this would all pass. I was soon going to be full time in the police department; I was also about to propose to my girlfriend, and soon after that, the plan was to have kids. My life was on the way up, but Mom’s kept going down.

While I was working on my family, Mom had found her own sort of family at the S.R.O. She got a new part-time job — working at the hotel’s front desk — and the next year, she had Thanksgiving catered for her inner circle of friends, 11 people. She purchased two turkeys from the diner where she once worked, pre-carved, with all the trimmings. The tab was an even $100, including paper plates and plastic utensils. Bigfoot brought a mover’s dolly and a little red wagon to help her haul the turkeys home from the diner.

The 11 friends she invited quickly became 15, and by the time they sat down for dinner, 20. Mom served turkey, plopped down mashed potatoes, and poured gravy on plates. The trimmings were set up buffet-style, and Bigfoot ate so much cranberry sauce that his tongue turned red. One resident complained that Mom had all the white meat and wasn’t sharing equally, but most everyone was grateful, especially for the pumpkin pie.

Mom was disappointed that her closest friend, Emilio, did not appear for the meal. She made up a plate for him and knocked on his door, but there was no answer. She wrapped it in aluminum foil, tucked it into a plastic bag and left it on the doorknob.

Back downstairs, one of the G&G brothers, Gary, told her that Emilio had been arrested. “He got busted last night at the meat markets.”

A group gathered around to listen in, and Gary got quite animated as he told the story. “He was robbin’ dudes at knifepoint! He’d been doin’ this a lot cuz a his crack habit, you know, and I knew they would catch him — undercover vice cop, that’s who. When Emilio pulled a blade on him, a bunch of cops swarmed all over the car they was in. He’s lucky they didn’t beat the bejesus out of him.”

Mom was very worried. She knew Emilio had two prior convictions and would be facing some seriously long prison time. She might never see him again. She went upstairs, took the bag of food off his doorknob, and threw it in the trash. She was more mad at him than sorry. She went up to her room to drink a few beers, then fell asleep with her clothes on. Mom spent the weekend alone in her room, devastated, then decided to visit Emilio in jail on Rikers Island. After producing identification at the visitors’ reception area, she boarded a bus that took her over the bridge, where she was searched and put on another bus to the detention center. After yet another search, she was led to the visit room and seated at one of the dozens of tables. More than an hour went by before Emilio entered and sat down across from her. He was wearing a gray jumpsuit and plastic slippers. “Not your best look,” Mom quipped. “Yeah, I know. Good to see you, Peggy. I heard I missed a good dinner.” “You did. I made up a plate for you and put it on your doorknob.” “Thanks, but by the time I get back, it will be long, long gone.” “

Why did you have to do this? You could have asked me for help. That’s what friends do, you know — help.”

“Sorry. I started smokin’ crack again. It’s such a great high, Peggy, the best. But don’t worry, they only got me for one robbery and another attempted. They said five years, but I turned it down cuz I know I can get less.” Emilio smirked, but Mom knew he was not in a position to game the system with two prior convictions. That drug had fried his brain. On the bus back over the bridge, something had changed in Mom. She didn’t want to end up like Emilio. She had to get out of the S.R.O. She got off the bus renewed, determined to make things better in her life. But I had seen that before, many times.

Nothing changed, of course. Each night, it was the same thing. Either she passed out in the lounge, in a drinking buddy’s room, or alone, in hers.

Terri was moving out. After improving her reading skills, she took an adult-education course at a nearby community center, and not long after, earned her high school equivalency diploma. She was moving into her boyfriend’s apartment in the East Village and had been hired as a receptionist at St. Vincent’s Hospital.

She made a point of thanking Mom before leaving, telling her, “I wouldn’t have been able to get it had you not helped me read betta’ Peggy. Thank you. Come visit me, when you can.” She gave Mom a piece of paper with her new address.

“I will, I will,” said Mom, giving Terri a motherly embrace. Mom never visited her. It would have been a painful reminder that she was still stuck at the S.R.O., while someone else, someone with barely the skills to get a high school diploma, had found a way out.

The true sign of an alcoholic is right after the morning pee; it’s the first thing they think about, having a drink, and they do. The crow’s-feet under Mom’s eyes were spreading, and her hair was thinning, losing its youthful luster. When the more caring of her drinking pals realized her decline, they stopped giving her freebies, even stole her stash. The manager of the hotel, Stewart, fired her from the front desk position after she kept missing shifts or coming down from her room late, unkempt, hungover, combative.

A few days after Stewart let her go, she was sitting in the day room doing and looking at nothing, when I walked in. It was 1988, and I’d recently gotten married. Mom had been living at the Jane West for six years at that point. She had not answered her phone lately and I was concerned, more than usual, this time.

“How the fuck are you, son?”

“What day is it, Ma?”

“Sunday?”

“Why aren’t you answering your phone?”

“Why aren’t you coming by the way you used to?”

“I’m married, Ma. It kind of occupies your time.”

“That woman is more important than your mother?”

“That’s not fair, Ma.”

“This fucking hellhole you let me live in is not fair.” This pushed a button in me. With much difficulty, I held in my response and left before starting a tirade.

Exactly two days later, I was back. This time I brought two colleagues with me: a detective and a civilian employee, both under the employment umbrella of the NYPD and assigned to what’s called the Early Intervention Unit. They were counselors who specialize in alcoholism and substance abuse. I made the introductions and then went down to the car while they spent some time with her.

They told me she kept repeating that everything was fine. “Why are you here? Why, why, why?” she said. They told her she would have to check in to a rehabilitation facility. Both counselors told her they had been through the program themselves, which helped. The female counselor helped Mom pack a bag, then take a shower.

When she and the counselor walked downstairs to the lobby, Bigfoot rushed up to Mom, giving her an enveloping hug goodbye. She cried the entire way to the hospital, where she spent nine days. The detox process required her body to be completely flushed of alcohol, which can be dangerous, even fatal. Her withdrawal symptoms included anxiety, insomnia, the shakes, hallucinations and profuse sweating. It was agonizingly difficult, but she got through it. At 11 in the morning on a beautiful Sunday in June, Mom was escorted out of the hospital by the same counselor who had accompanied her in. She felt rejuvenated during the drive along the familiar city streets. They cut through Central Park, passing a horse and carriage clomping along, joggers, office workers buying food at carts, couples picnicking, and mothers talking, laughing, pushing strollers.

Life is always going on somewhere, without you, she thought.

Mom spent 37 days at the Smithers Alcoholism Treatment Center in an old, opulent mansion on the Upper East Side. She was optimistic, focused and, in general, happier. My wife, Michelle, was two months pregnant, and it looked like maybe little Ray Jr. would have a doting, cookie-baking grandma after all.

Mom took a typing refresher course and finished top of her class, 120 words per minute. She found a job at the Time Life corporation in Midtown. Her assignment would be in a secretarial pool on the 19th floor.

For a few months, everything went smoothly. We had twins and Mom called to check in on the boys every day. She visited and we had picnics in the park. I tried to convince her to move out of the S.R.O., but she wouldn’t budge.

Then one day all hell broke loose.

Richie, the uniformed elevator attendant, snapped, after Bigfoot, who was dead set against any of his friends using drugs, took a baggie of Richie’s heroin and flushed it down the toilet. Richie confronted Bigfoot and, not feeling satisfied with the response, stabbed him in the gut. My mom was right there and saw it all.

When he heard the police sirens on their way, Richie sliced his own throat. Some of his blood splattered on Mom, adding to the already grisly scene. Luckily, Bigfoot survived the attack. I don’t know if Richie did.

But the incident sent Mom spiraling downward even further.

She was headed home from an appointment with her therapist when she got sucked into a pub and ordered a Guinness, then another, then two glasses of Glenfiddich single malt scotch. To finish up she ordered five pours of Bailey’s Irish Crème, over the rocks. Needless to say, she was smashed and had to be carried out into a cab. The cabbie, afraid she was going to vomit and not interested in her belligerence, quickly kicked her out. She stumbled down the street and a police car pulled up. One of the officers got out and approached her.

“Fuck off, pig!” she yelled.

He grabbed her arm, handcuffed her, and guided into the back seat of the police car. “Fuck off!” Mom yelled as she was brought into the NYPD’s 6th precinct.

The desk sergeant was not in a pleasant mood. “I’ve heard that before, lady.”

Somehow, from her purse, she produced the little mini-badge I’d given her. “My get out of jail free card.”

The desk sergeant took the badge and studied it. “Hey, I’ve heard of you before. I’ve met your son. He’s at the 120, in Staten Island.”

“You gots it, muddafuckas.”

“What is wrong with you, Mrs. Hannity?” She answered, with a hiccup,

“I’m a rehab survivor.”

Fortunately, the desk sergeant called me and I came down to the station. Nearly in tears, I said, “Ma, what have you done?”

All six officers in the room stared, cringed, sympathized with me.

“Hi, son. I think I had too much to drink. Looks like old times again.” It was pouring rain as we got into my car.

“When I’m going to see the boys?” she asked. “They’re so cute with the little bums.”

I pulled up to the hotel and double-parked. I carefully escorted her up to her room, took her shoes off, and helped her into bed. I put a glass of water on her nightstand. She passed out in less than a minute.

With Bigfoot in the hospital, his absence really sunk in. Had he still been here, I could have asked him to check up on her. He was like a superhero when Mom’s health was at stake. I really missed the big oaf now. I sat in a chair in her room, for over an hour. She got up once to vomit in the bathroom. She didn’t even see me. After her head hit the pillow again, I left.

A week later, the same thing happened again. This time, I was not contacted. She was arrested, given a desk appearance ticket and a court date. She received a sentence, which was to report to the New York City Sanitation garage, within walking distance of the S.R.O., for community service. She was assigned to be a neighborhood street cleaner for three eight-hour shifts, totaling 24 hours. By that Friday, Mom had completed her community service and went to the criminal courts building to hand in her proof of attendance. The woman behind the desk gave her a validation copy and another form stating that she had completed her sentence. Mom left the building with a feeling of accomplishment. On the way home, she stopped at the corner bodega near the hotel intending to buy a six-pack of Miller, but somehow managed to find the strength not to.

On New Year’s Eve, she drank so much she passed out. She woke up in the lounge, with a party hat on, and called me.

“Happy New Year, son. How’s life?”

“Life is fine, Ma. What’s up with you?” I could tell by her voice that she was in a troubled mood.

“Nothing. Just spoke with my boss at Time Life. He said they didn’t need me anymore, that my temporary assignment was done. I’m on the short list to come back soon.”

“OK, that’s good.” That was not good. She was the best typist in the pool. I sensed in her voice she had been fired.

Mom’s life spiraled even further out of control. She spent all of her time at the hotel. She made new friends, who were even more troublesome, if you can imagine that, and drank to excess every day. She called at least once a week, but neither Michelle or I answered the phone when we saw it was her. She left messages on our answering machine that were difficult to understand.

On April 5, 1992, Mom was in the day room with “friends,” drinking and laughing. Suddenly, she experienced a very strange feeling. Her face felt as though it was turning to stone. She got up and made a call on the pay phone, to me. As she was leaving a message, I picked up. Calmly, she said, “Ray, it’s time.”

“Time for what, Ma?”

“Don’t worry, because things always work out in the end. I love you,” and she hung up the phone.

The next day, I decided to visit her at the S.R.O. I walked past Stewart, who was reading a newspaper at the front desk, but before I got to the stairwell, he stopped me. “Ray, your mother left last night.” “What do you mean, she left?”

“Here.” Stewart held out an envelope for me to take. “She gave this to me, to give to you.”

I opened the letter and sat down in a wobbly chair to read it:

Dear Ray,

I’m sorry it had to be this way, but it’s for the best. I can’t live like this anymore, bringing you down when you are already so tall. I know I’ve worn out my welcome. I’ve decided to try and make a new life for myself, whatever that may be. I bought a decent travel suitcase, pooled all my savings, and so by the time you read this, I will be on a Greyhound bus headed west. I’ve always wanted to see America. Everyone says New York is New York, nothing like the rest of the nation, so I guess then I don’t really know the world, or the real America. I’ll bet there are interesting people out there just like us, with similar joys and struggles. I’d like to meet them. I hope, one day, to reach out to you to give you better news. Please remember that I will always love you and your wonderful family. I’ve enclosed some savings bonds for the boys. Have Stewart give you the key to my room. Anything worth taking is yours.

Love, Mom

I stared at the letter for what seemed the longest time, not knowing what to think or do. She had enclosed two U.S. savings bonds for the boys, $500 each. I asked Stewart for Mom’s room key, walked up the four flights of stairs and unlocked her door. What I saw inside left me speechless. On the bed were photos of me as a child, my chewed-up baby rattle and tattered teddy bear, all neatly wrapped in clear plastic. I couldn’t believe that after all she had been through, she kept these things from my childhood. This meant, while homeless, she was carrying these things around.

I made a quick inventory of the room and discovered a stack of spiral notebooks that had functioned as her diary for the last few years (and are the source for much of the material in this story, along with various other notes she saved, scribbled on bits of paper and napkins). I packed them all into several shopping bags. Since I’d left the door open, I noticed three people trying to peek in from the hallway. One of them asked if I was taking the radio, but I didn’t bother to answer. I left the room unlocked so the resident scavengers could take whatever was left, which they started to do even before I got to the stairwell. When I got to the bottom, I peeked into the lounge one last time. I could only see a bedraggled man, sleeping in a chair, with a book on his lap. I went back into the lobby and looked up at the garish, dusty chandeliers and smiled. I sighed, chuckled, and walked out the double front door, gleeful to never again have to set foot in that godforsaken place, the Jane West Hotel.

I didn’t hear from Mom until several years later. She was living in another S.R.O., on the Upper West Side, this one designed for tenants over the age of 50. She looked much older and had gained substantial weight. I almost didn’t recognize her at first. She told me she had traveled to Nashville, New Orleans, Chicago, San Francisco, and a few other smaller places, like Topeka, Kansas, and Cheyenne, Wyoming, picking up cash along the way by waitressing or taking on odd jobs like handing out advertising leaflets on street corners.

It was strange seeing her again, almost like starting all over. Even though her health was poor, she seemed more upbeat, consistent in demeanor. But she had lost the spark in her step, and with the added weight, was not too mobile. I allowed her to come by to see Michelle and the boys, who were in grade school now. Ultimately, we even let her babysit them twice a week. It worked out quite well, considering her prior behavior. She wasn’t perfect, but responsible enough. She was fine for nearly a year, but then the demons came back. She began to talk nonsensically, rambling on about things which were mostly of concern only to her.

I transitioned to the Fire Department and was working out of Engine 9, in Chinatown, on September 11, 2001. Of course, we all know what happened that day. Our engine company was one of the first on the scene. I miraculously survived the collapse of the North Tower by running out of the lobby as the building came down, diving under a tow truck not far from the front door. I was OK, relatively, after crawling out from a pile of toxic rubble. Mom was now back to her old self. The late-night calls from the police and hospital emergency rooms were getting more frequent. In May of 2002, she was admitted to St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital with a multitude of maladies. When I arrived at the hospital, I was told her kidneys and liver were failing. They promised to do whatever they could, though, inevitably, at some point, her body would simply stop.

On Mother’s Day, May 11, 2002, when my wife and I arrived at the hospital, the doctors informed me that Mom had lapsed into a coma and multiple bodily functions had shut down. She was being kept alive only by a respirator. After conferring with them, we agreed the respirator should be shut off. Her mother, my grandmother, had also died on a Mother’s Day, May 11, after succumbing to cancer 17 years earlier. They’re buried beside one another in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, mother and daughter, hopefully, finally, at peace. As for the S.R.O? In 2008, the Jane West Hotel was purchased by developers for a cool $27 million and transformed into a chic boutique hotel. The first-floor lounge where my mother spent so many days socializing is now a sleek restaurant where you can enjoy black truffle shavings over “peasant pasta” before settling down for a night in one of the vintage-wallpaper-lined guestrooms. You’ll even get access to the shared unisex bathroom.

Ray W. Hayden is a veteran of the NYPD and NYC Department of Corrections, where he amassed numerous medals for bravery, and the FDNY, where he served as a first responder on September 11.

Nicole Rifkin is an award-winning Canadian American illustrator based in Brooklyn, NY.

Brendan Spiegel is the Editorial Director and co-founder of Narratively.