How a Spy Known as the ‘Limping Lady’ Helped the Allies Win WWII

A new biography explores the remarkable feats of Virginia Hall, a disabled secret agent determined to play her part in the fight against the Nazis

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/0e/d90e4c27-750c-4326-b268-e6513f447b4e/22-lind-new-ii.jpg)

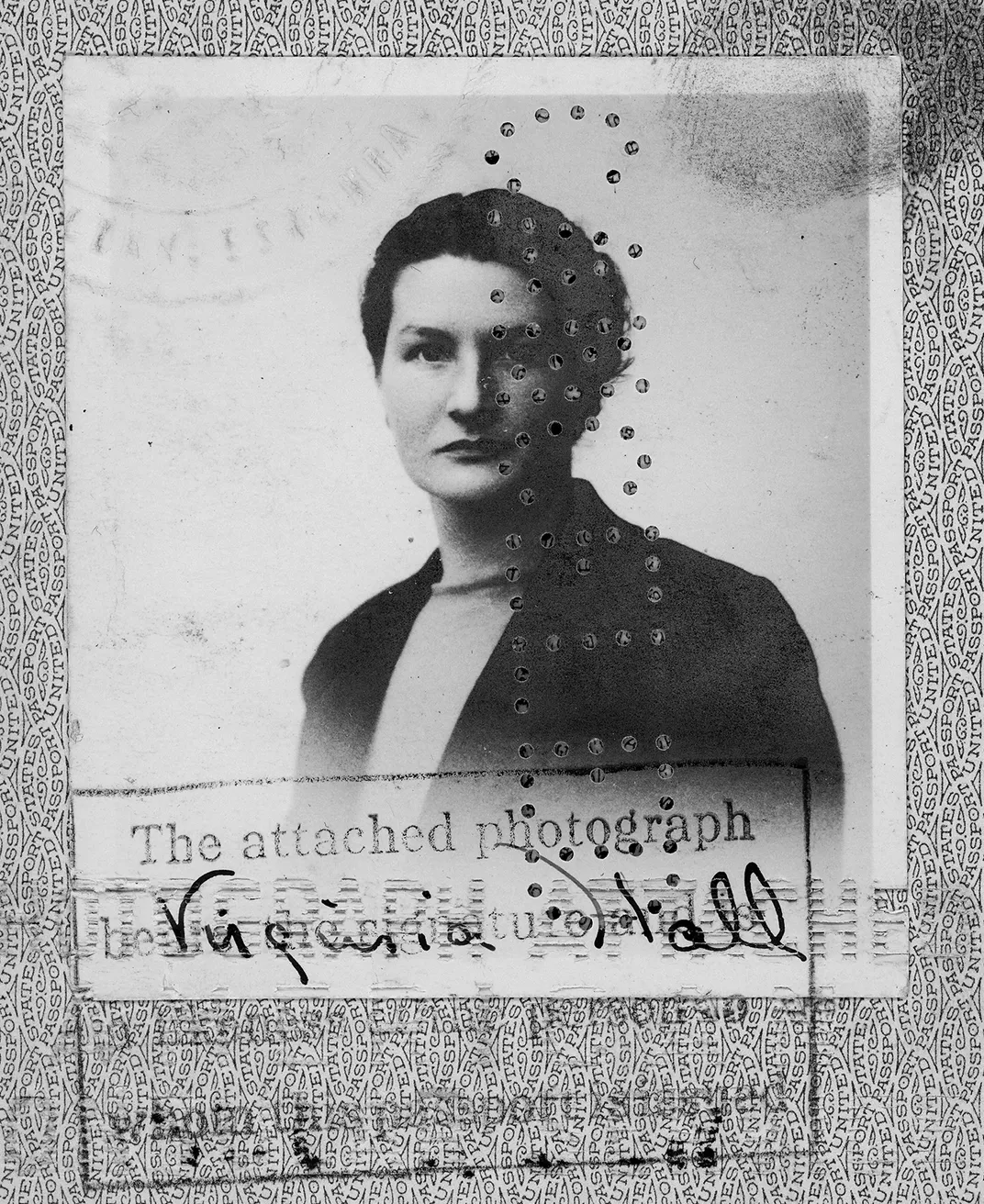

In early September 1941, a young American woman arrived in Vichy France on a clandestine and perilous mission. She had been tasked with organizing local resistance networks against France’s German occupiers and communicating intelligence to the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the fledgling British secret service that had recruited her. In reality, however, Virginia Hall’s supervisors were not particularly hopeful about her prospects; they didn’t expect her to survive more than a few days in a region teeming with Gestapo agents.

At the time, Hall admittedly made for an unlikely spy. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s war cabinet had forbidden women from the frontlines, and some within the SOE questioned whether Hall was fit to be operating in the midst of a resistance operation. It wasn’t just her gender that was an issue: Hall was also an amputee, having lost her left leg several years earlier following a hunting accident. She relied on a prosthetic, which she dubbed “Cuthbert,” and walked with a limp, making her dangerously conspicuous. Indeed, Hall quickly became known as the “Limping Lady” of Lyon, the French city where she set up base.

Listen to Sidedoor: A Smithsonian Podcast

Hall, however, had no intention of letting Cuthbert stop her from playing her part in the Allied war effort, as journalist and author Sonia Purnell reveals in an electrifying new biography, A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II. Born to a wealthy Maryland family, Hall was clever, charismatic and ambitious—traits that were not always appreciated by her contemporaries. Before the outbreak of the war, she had travelled to Europe with dreams of becoming a diplomat, but was consistently assigned to desk jobs that failed to satisfy her. Following the amputation of her leg in 1933, when she was just 27 years old, Hall’s application to a diplomatic position with the U.S. State Department was explicitly rejected due to her disability. Spying for the SOE offered a way out of what Hall considered a “dead-end life,” Purnell writes. She was not going to squander the opportunity.

Hall didn’t just survive the wartime years under constant threat of capture, torture and death; she also played a crucial role in recruiting large networks of resistance fighters and directing their assistance to the Allied invasion. Among the secret operatives who adored her and the Nazis who hounded her, Hall was legendary for her gutsy, cinematic feats. She broke 12 of her fellow agents out of an internment camp, evaded the treachery of a double-crossing priest and, once her pursuers began to close in, made an arduous trek over the Pyrenees into Spain—only to return to France to resume the fight for its freedom.

And yet, in spite of these accomplishments, Hall is not widely remembered as a hero of the Second World War. Smithsonian.com spoke to Purnell about Hall’s remarkable but little-known legacy, and the author’s own efforts to shine a light on the woman once known to her enemies as the Allies’ “most dangerous spy.”

In the prologue to A Woman of No Importance, you write that you often felt as though you and Hall were playing a game of “cat and mouse.” Can you describe some of the obstacles you encountered while trying to research her life?

First of all, I had to start with about 20 different code names. A lot of the times that she is written about, whether it’s in contemporary accounts or official documents, it will be using one of those code names. The other thing was that a lot of files [pertaining to Hall] were destroyed—some in France in a fire in the 1970s with a lot of other wartime records. That made things pretty difficult. Then the SOE files, some 85 percent of those had been lost, or are still not opened, or are classified or just can’t be found.

There were a lot of dead end alleys. But there was enough to pull this all together, and I was particularly fortunate to find this archive in Lyon, put together by one of the guys that Hall fought with in the Haute-Loire [region of France]. He was able to look at a lot of these files before they disappeared, and he had contemporary accounts of a lot of the people that she fought alongside. So I was extremely lucky to find that, because it was an absolute treasure trove.

You quote Hall as saying that everything she did during the war, she did for the love of France. Why did the country hold such a special place in her heart?

She came [to Paris] at such a young age, she was only 20. Her home life had been quite restrictive ... and there she was in Paris, the great literary, artistic and cultural flowering during that time. The jazz clubs, the society, the intellectuals, the freedoms, the emancipation of women—this is quite heady, quite intoxicating. It really opened her eyes, made her feel thrilled, and stretched and inspired. That sort of thing in your 20s, when you’re very impressionable, I don’t think you ever forget it.

Operating in a war zone with a mid-20th century prosthetic could not have been easy for Virginia. What was life like with “Cuthbert” on a daily basis?

I managed to find a prosthetics historian at one of the museums here in London who was incredibly helpful. He explained to me exactly how her leg would have worked, what the problems were, what it could do and what it couldn’t do. One of the problems was the way it was attached to her, with these leather straps. Well, that might be OK if you’re just walking a short distance in mild weather, but when it’s really hot and you’re climbing up or down steps, the leather would chafe your skin until it was raw and the stump would blister and bleed.

It would have been very difficult in particular going down steps because the ankle doesn’t work in the way that our ankles do, and it would be quite difficult to lock. So she would always feel very vulnerable to falling forward. That would have been a very big danger for her at all times, but then magnify that for crossing the Pyrenees: the grinding, relentless climb and then the grinding, relentless descent. She herself said to her niece that this was the worst part of the war, and I can believe that. It was just phenomenal that she made that crossing.

Hall pulled off so many incredible feats during the war. What, in your opinion, was her most important accomplishment?

That’s a difficult one, it’s a competitive field. I suppose the one that you can grab as being standalone, understandable and also spectacular was how she managed to break those 12 men out of a prison camp: the Mauzac escape. The cunning, and the organization and the courage—just the sheer chutzpah that she had in springing them out ... It is quite an extraordinary tale of derring-do. And it was successful! Those guys made it back to Britain. We hear about a lot of other wartime escapes that ultimately ended in a failure. Hers succeeded.

Another of Hall’s feats was pioneering a new style of espionage and guerilla warfare. Does her influence continue to be felt in that realm today?

I spent a day at [CIA headquarters at] Langley, which was really fascinating. Talking to people there, they pointed to Operation Jawbreaker in Afghanistan, and how they drew on the processes that really she pioneered: How do you set up networks in a foreign country, bringing in locals and perhaps preparing them for some big military event later on? They took Hall’s example. I’ve heard from other people involved in the CIA who said she still is mentioned in lectures and training there today. Not that long ago they named one of their training buildings after her. Clearly, she has an influence to this day. I’d love to think she knows that somehow, because that’s pretty cool.

Today, Hall is not particularly well known as a war hero, in spite of her influence. Why do you think that is?

Partly because she didn’t like blowing her own trumpet. She didn’t like the whole obsession with medals and decorations; it was about doing your duty, and being good at your job and earning the respect of your colleagues. She didn't go out of her way to tell people.

But also, a lot of other SOE female agents who came in after her died, and they became these quite well-known tragic heroines. Films were made about them. But they achieved nothing like what Hall did … It was difficult to pigeonhole her. She didn't fit into that conventional norm of female behavior. In a way she wasn’t a story that anyone really wanted to tell, and the fact that she was disabled as well made it even more complicated.

When I was thinking of doing this book, I took my sons to see Mad Max: Fury Road with Charlize Theron, and I noticed that her [character’s] forearm was missing, and yet she still was the great hero of the film. And I thought, “Actually, maybe now that Hollywood is doing a film with a hero like that, finally we’re grown up enough to understand and cherish Virginia’s story and celebrate it.” It was that night really that [made me think], “I’m going to write this book. I really want to tell the world about her, because everyone should know.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.