How Ida Holdgreve’s Stitches Helped the Wright Brothers Get Off the Ground

In 1910, Orville and Wilbur Wright hired an Ohio seamstress, who is only now being recognized as the first female worker in the American aviation industry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/44/47/44477f9a-5b64-4e05-ae5a-a06f1f64e4b2/ida_holdgreve.jpg)

Around 1910, Ida Holdgreve, a Dayton, Ohio, seamstress, answered a local ad that read, “Plain Sewing Wanted.” But the paper got it wrong. Dayton brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright were hiring a seamstress, though the sewing they needed would be far from plain.

“Well, if it’s plain,” said Holdgreve years later, recalling her initial thoughts on the brothers’ ad, “I can certainly do that.” The quote ran in the October 6, 1975, edition of Holdgreve’s hometown newspaper, The Delphos Herald.

The Wright brothers, in fact, wanted someone to perform “plane sewing,” but in 1910, that term was as novel as airplanes themselves—a typesetter could have easily mixed up the spelling. And while Holdgreve lacked experience with “plane sewing,” so did the vast majority of the world. She got the job, and the typo turned a new page in women’s history.

“The fact that, early on, a woman was part of a team working on the world's newest technology is just amazing to me,” says Amanda Wright Lane, the Wright brothers’ great-grandniece. “I wonder if she thought the idea was crazy.”

By the time Holdgreve answered the brothers’ ad, seven years had passed since their first 1903 flight, yet Wilbur and Orville were only recent celebrities. While the original Wright Flyer showed proof of concept, it took another two years to build a machine capable of sustained, maneuverable flight—a practical airplane—the 1905 Wright Flyer III. Finally in August 1908, after being stymied by patent and contract issues, Wilbur made the first public flights at Hunaudières racecourse near Le Mans, France; then and there, the brothers became world famous. The following year, Wilbur circled the Statue of Liberty during New York’s Hudson-Fulton Celebration.

***

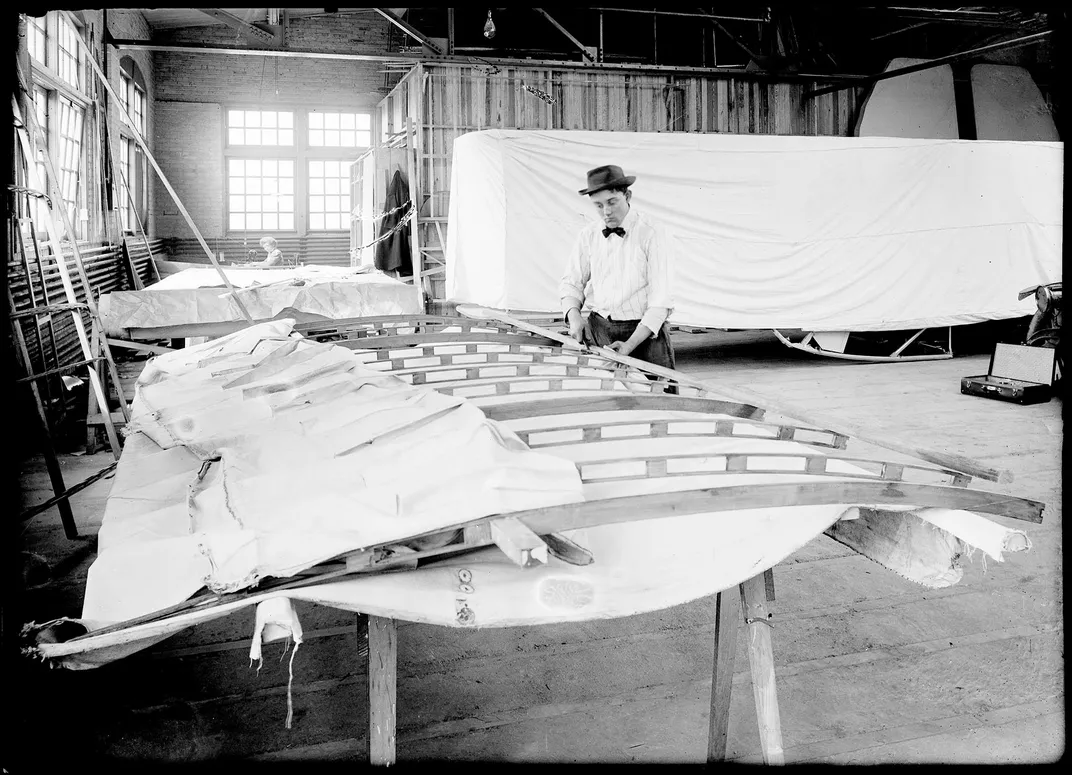

In 1910 and 1911, two odd buildings began to rise a mile-and-a-half west of the Wright brothers’ West Dayton home. Bowed parapets bookended the long one-story structures, their midsections arching like the crooks of serpents’ spines; wide windows reflected the pastoral world outside. This was the Wright Company factory, the first American airplane factory, and behind the buildings’ painted brick walls, Holdgreve sewed surfaces for some of the world’s first airplanes, making her a pioneer in the aviation industry.

“As far as I know, she was the only woman who worked on the Wright Company factory floor,” says aviation writer Timothy R. Gaffney, author of The Dayton Flight Factory: The Wright Brothers & The Birth of Aviation. “And she was earning her living making airplane parts. Since I haven’t found a woman working in this capacity any earlier, as far as I know, Ida Holdgreve was the first female American aerospace worker.”

***

Holdgreve was born the sixth of nine children on November 14, 1881, in Delphos, Ohio. For years, she worked as a Delphos-area dressmaker before moving 85 miles south to Dayton in 1908; two years later, as a 29-year-old single woman, she began work at the Wright Company factory. Dayton was a rapidly growing city during these days, yet the brothers opted to erect their factory in a cornfield three miles west of the downtown area—the setting hearkened back to Holdgreve’s home.

“Delphos is surrounded by corn,” says Ann Closson (Holdgreve), Holdgreve’s great-grandniece, who grew up in Delphos. “It’s a small farming community.” Closson learned of Ida from her dad when she was 12 years old, but her cousin, now in her 40s, just found out about their ancestor and her role in aviation history. “The story is so inspiring,” she says. “Ida went on this journey to work in the city—at the time, that wasn’t very acceptable for a young woman.”

Mackensie Wittmer is executive director for the National Aviation Heritage Alliance, a nonprofit that manages the National Aviation Heritage Area (NAHA), which spans eight Ohio counties tied to the Wright brothers’ legacy. “This is a non-clerical job, which is unique,” she says, of Holdgreve’s position. “Ida’s on the floor—she’s in the trench—working with men to build some of the world’s first airplanes.”

At the Wright Company factory, surrounded by the thrum of motors and the clamor of hand-started propellers, Holdgreve fed her machine two large spools of thread, sewing light cream-colored fabric into airplane wings, fins, rudders and stabilizers. All told, the firm manufactured approximately 120 airplanes in 13 different models, including the cardinal Wright Model B, the Model C-H Floatplane and the advanced Model L. Up to 80 people worked at the Wright Company factory, building planes for civil and military use—these employees formed the first American aerospace workforce.

“When you think about these people, you realize they were part of a local story, but they were also part of a national story, an international story,” says Dawne Dewey, who headed Wright State University’s Special Collections & Archives for over 30 years. “These are hometown people, ordinary people. They had a job, they went to work—but they were a part of something much bigger.”

***

Duval La Chapelle—Wilbur’s mechanic in France—trained Holdgreve. Only two years earlier, La Chapelle had witnessed the Wrights become overnight celebrities; now, the French mechanic was training Holdgreve to cut and sew cloth, to stretch it tightly over the plane frame so it wouldn’t rip in the wind.

“When there were accidents,” Holdgreve recalled in the October 6, 1975, edition of The Delphos Herald, “I would have to mend the holes.”

Earlier, she told the newspaper of her impressions and interactions with the Wright brothers. “Both boys were quiet,” she said. “Orville wasn’t quite as quiet as Wilbur. At different times I talked with Orville and got acquainted. They were both very busy, not much time to talk to the people there. But they were both nice.”

Orville was notoriously shy, so Holdgreve must have made him comfortable. And at the time, Wilbur, the duo’s mouthpiece, was engaged in the brothers’ infamous “patent wars,” so perhaps his mind was elsewhere. The constant legal battles over the Wrights’ intellectual property seemed to weaken Wilbur, and in late April 1912, only two weeks after his 45th birthday, he contracted typhoid fever. One month later, on May 30, 1912, Wilbur died at home.

“For Uncle Orv, it was a devastating blow,” says Wright Lane. “Their thinking, their hobbies, their intellect—they were always right in sync.”

After Wilbur died, Orville was left to run the Wright Company alone. Not only was he grieving his brother—his closest friend—but he also had lingering back and leg pain from his 1908 airplane crash at Fort Myer, Virginia. Orville “seemed somewhat lost” noted Wright Company manager Grover Loening, who had just graduated from Columbia University with the first-ever aeronautical engineering degree. After Wilbur died, Orville dragged his feet on business matters and stopped attending Wright Company factory board meetings.

“If Wilbur had survived, I always wondered if they would have found some other wonderfully interesting problem to solve,” says Wright Lane. “But I don't think Orville had it in him without the back and forth with his brother. They were always bouncing ideas off one another. And arguing.”

On October 15, 1915, having lost both his brother and flair for business, Orville sold the Wright Company. But neither Orville, or Holdgreve, were entirely out of the airplane business.

***

In 1917, Dayton industrialist Edward Deeds co-founded the Dayton-Wright Airplane Company and enlisted his good friend Orville as a consulting engineer. During World War I, Dayton-Wright produced thousands of planes, and at the company’s Moraine, Ohio, plant, a lively young woman from Delphos supervised a crew of seamstresses.

“I went to work … as a forewoman for girls sewing,” said Holdgreve. “Instead of the light material used for the Wright brothers, the material was a heavy canvas, as the planes were much stronger.”

According to Gaffney, Holdgreve was managing a crew of women sewing the fabric components for the De Havilland DH-4 airplanes being produced in Dayton. The Dayton-Wright Company, in fact, was the largest producer of the DH-4: the only American-built World War I combat aircraft. “She was Rosie the Riveter before there were airplane rivets,” says Gaffney. “She was involved in the war effort.”

After the war, Holdgreve left the aviation industry to sew draperies at Rike-Kumler Company in downtown Dayton—the same department store where the Wright brothers purchased the muslin fabric for the world’s first airplane, the 1903 Wright Flyer.

Years later, Holdgreve looked back on her experience in the aviation industry. “At the time,” she recalled, “I didn’t realize it could be so special.”

Holdgreve lived out her days in Dayton, and at age 71, retired from sewing to care for her sister. (At age 75, neighbors could see her cutting her lawn with a push mower). Holdgreve’s story was known in local circles, though not widely. Then in 1969, the 88-year-old fulfilled a lifelong dream. “I’ve wanted to go for such a long time,” Holdgreve told the Dayton Daily News in its November 20, 1969, edition. “And I’m finally getting to do it.”

While the spry woman hand-sewed some of the world’s first airplanes, she had never flown.

Wearing spectacles, black gloves, a thick winter coat and a black cossack hat, Holdgreve climbed aboard a twin-engine Aero Commander piloted by Dayton Area Chamber of Commerce Aviation Council Chairman Thomas O. Matheus. “I couldn’t hear so well up there,” Holdgreve said after Matheus flew over the Wright Company factory in West Dayton. “The clouds look just like wool.”

The story was wired across the country, making Holdgreve a fleeting celebrity. “An 88-year-old seamstress,” reported The Los Angeles Times on November 23, 1969, “who 60 years ago sewed the cloth that covered the wings of the Wright brothers’ flying machines, has finally taken an airplane ride.”

“You know,” she told the Dayton Journal Herald after the flight. “I didn’t think they would make such a big thing out of it. I just wanted to fly.”

On September 28, 1977, Holdgreve died at age 95. Over the years, her story faded, only to resurface in 2014 when the National Aviation Heritage Alliance and Wright State University’s Special Collections & Archives jump-started the Wright Factory Families project.

“It grew out of an idea Tim Gaffney had,” says Dewey. “He was working for NAHA at the time, and he was really interested in exploring the Wright Company factory workers, and what their stories were. Through the project we were connected to Ted Clark, one of Holdgreve’s family members, and he gave us some old clippings on Ida.”

After more than a century, the Wright Company factory still stands. Repurposed for various uses, the building’s tale was lost with time. But in recent years, Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, NAHA and other organizations have sought to preserve the famous factory. In 2019, the buildings were placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

While the site is currently closed to the public, the National Park Service hopes one day guests will walk the old Wright Company factory floor. Maybe then, Holdgreve, who for years diligently sewed in the building’s southwest corner, will get the credit she’s due.